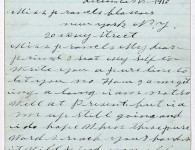

Fields Cook was born into slavery in King William County and rose to become a prominent African American leader in Richmond and Alexandria. In 1847 he began writing a narrative of his life, one of the longest manuscripts known to have been composed by an enslaved Virginian. Part of the his memoir survives at the Library of Congress.

He received permission about 1834 to live in Richmond, where he presumably participated in the illegal but common system of self-hiring. He married an enslaved domestic servant named Mary and became the father of at least three children. Gaining his freedom by 1850, he had managed by 1860 to free most of his family.

After the Civil War, Cook became a Baptist minister and emerged as one of the most important African American leaders in Richmond. In 1865 when federal military authorities imposed harsh regulations on freed-people, Cook and other leaders collected evidence of military and civilian misbehavior and called a mass meeting. Cook chaired the delegation chosen to present their case to the governor and to the president of the United States.

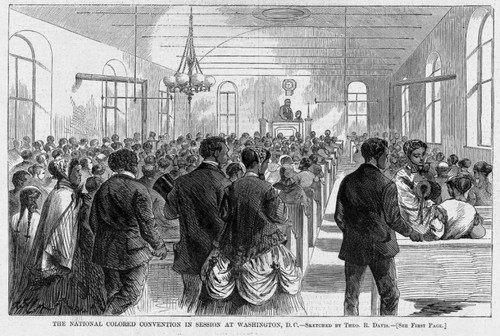

Cook represented Richmond in the first state convention of African Americans. He wrote the convention’s address to the public in which he argued that African Americans deserved full equality and must have the vote for their own protection. Cook’s radical vision was at variance with ideas of subservience that the state’s white leaders offered. In 1869 Cook attended the National Convention of the Colored Men of America in Washington, D.C., and was elected to its national executive committee. From 1867 to 1869 Cook worked for the Republican Party. He had an uneasy relationship with the Radical Republican leaders, as he favored a more inclusive party than they did. As an independent candidate for a seat in Congress in 1869 Cook received less than 1 percent of the vote.

In 1870 Cook and his wife moved to Alexandria. As prominent there as he had been in Richmond, Cook remained in the Baptist ministry and was active in politics, supporting the Readjusters during the 1880s. He died in 1897, five years before Virginia stripped African American men of the vote—the franchise for which Cook had fought for three decades, claiming it as a right and a necessity. He was buried probably in Alexandria’s Douglass Memorial Cemetery, of which he was a founder.

source:

https://www.encyclopediavirginia.org/Cook_Fields_ca_1817-1897

1 Comment

Cook, was way ahead of his time. We have so many unsung heroes.