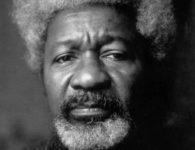

Photo credits: St. John’s Confidential File

In the intertwined worlds of stand-up comedy, comedic television shows, and films, as well as audio albums, one unapologetically black man’s name rings bells throughout the whole entertainment industry: Paul Mooney.

On August 4, 1941, Mooney was born Paul Gladney in Shreveport, Louisiana. However, less than a decade after his birth, Oakland, California became his home. It is also the city where Mooney started off as a comedic host, of sorts. It was a front-and-center gig, which introduced Oakland to his entertaining personality. However, it was not as star-studded as the television, film, and the world-renowned live stage circles where Mooney eventually became a gatekeeper. Nonetheless, as a former hilarious ringmaster of a circus, he still ran the show.

Mooney’s ringmaster gig in Oakland during the olden times was also where he first honed the use of his most formidable weapon: A pen. Mooney’s comedic writing style had the versatility of a doppelganger. He wrote believable characterization for his routines, which impersonated the tones of both genders. Eventually, his uncanny and undeniable talent caught the eye of a comedy juggernaut who was still in the early stages of his career: The late but still legendary Richard Pryor. Mooney started off writing jokes for Pryor.

However, in due time, Mooney’s balloons of comedic dope Pryor sold to packed pavilions onstage raised in demand. In order to feed it with more supply, Pryor promoted Mooney to right-hand man as his writing partner. It was a position that stuck with Mooney like Gorilla Glue from then on. From yesteryear until this day, fans and the entertainment news media have infirmly identified the former ringmaster as Pryor’s carte blanche writing plug. If one validates everything said as true, voicing their truth with no research could make another person think that was Mooney’s sole job.

But that is not true. In its chronologic linear totality, Mooney’s legacy in entertainment teaches a lesson. It shows how longevity’s big payoffs come in perpetuity. They are paid only with sacrifice. Mooney’s exemplary aspects show what aspiring builders in any career are scared to do–or flat-out hate to do: Pay dues, show substance, and decline major time in the limelight so someone else can have it. Legendary comedians from Black Hollywood and the white-heated predominant sector of mainstream Tinseltown had Mooney as their original benefactor.

Robin Williams, Sandra Bernhard, Marsha Warfield, John Witherspoon, Tim Reid, and more have the man often relegated as Pryor’s writer to thank when it came to getting their first big check. Also, when analyzing the caliber and dynamics of the comedy television shows (where Mooney ran the writing teams) you might get schooled.

All-time jewels from the tube, such as Redd Foxx’s Sanford and Sons, Good Times, and later In Living Color (produced by the Wayans house that Keenan-Ivory built) are just a few places where Mooney’s pen reeled the money in. However, Mooney’s career triumphs did not transpire without controversy. Ultimately, Mooney’s storied connection to Pryor in the earlly1980s would attempt to haunt him–after a former bodyguard who was around back then came forward with a claim of what could have been career-ending damnation for anyone else.

Rashon Khan (the bodyguard) told Comedy Hype in an exclusive 2019 interview that Mooney sexually abused Pryor’s underage son, Richard Pryor, Jr. Khan also said that the elder Pryor put a contract hit out on Money’s head. But an untimely incident foiled the plot. Richard Pryor, Jr. later came out to speak for himself. The son of an icon said that he was molested during that time and was deeper into hard-core drugs than one could imagine. However, he stopped very short of officially branding Mooney as the one who committed the alleged criminal act of lewdness.

Spiraling whispers about Mooney’s sexuality sparked question marks publicly. But he never seemed to care about it, nor did he explain himself over it. He slyly smiled at a fellow comedian who addressed it during a televised comedy show. Earthquake called Mooney his “gay uncle” during a comedic television roasting session. In all, TV One’s “Toast to the Roast.” was a sport for their craft. Mooney maintained demeanor shaking his head at Earthquake with a “n*gga, you done lost your damned mind” look on his face.

Though Mooney’s Pryor Jr. drama came and went, the black community has a repugnantly sick secret, which surrounds girls, boys, men, women, the straight, and the gay. All of these categorically defined sectors of the black race (age, gender, sexual preference, etc.) are included in the victim and offender classifications in countless cases. Sexuality debates or puns for fun among blacks is one thing. Plenty of lip service has gone on about it.

But too many members of the early puberty and pre-puberty populations of black youths are sexually molested–by black teen or adult offenders all the time without much mention. That is a shameful reality, which blacks internally have allowed with impunity. Mooney’s negative press involving his own allegations of child rape created a temporary catalyst for chatter about this black-owned issue. However, the conversation must be sustained or there will be internal consequences that black people themselves will suffer. Some of it is coming to pass.

For the most part, Mooney’s presumably neutral stance about projecting his sexuality is on code. He did not play when it came down to professing the whole concept of maintaining and promoting black genealogical survival. To a biogeographical science, not a political one, Mooney gave the real reason why whites are scared: the biological threat of being closer to extinction, which is brought on by their recessive genealogy. Politics, economics, and even analyzing the historically triggering era of slavery do not offer the same depth that cracking the gene code on race does.

When Mooney would roll solo representing himself on the comedy tip, he hilariously but dead seriously, drained fully automatic clips at white America, mainstream Hollywood, and even the black people he didn’t view as relevant to his race’s cultural crest. During a routine on the “Ask a Black Dude” segment of the Dave Chapelle Show, Mooney’s character (named Negrodaumus) was asked a scripted series of rapid-fire questions, But Mooney was firing right back totally freestyle. One question was: “Why do white people love Wayne Brady?”

Because he makes Bryant Gumbel look like Malcolm X,” Mooney answered with laughter storming after him.

In 2014, an announcement was made by one of Mooney’s family members that he was diagnosed with prostate cancer, one of the menacing disease’s most lethal forms. This would be the final adversity, which served as Mooney’s deciding factor to end his illustrious career at last. The pioneering culture critic, racially-keen philosopher, and bold social commentator would hang on for seven more years. Mooney died of a heart attack on May 19, 2021, in his beloved city of Oakland.

The lightning rod legend of comedy was 79 years of age.

No comments