Photo credits: Frank Leslie’s Illustrated Newspaper

After the Civil War, the Democratic Party designed its Mississippi Plan of 1875. This order to overthrow the Republican Party in Mississippi called for systematic acts of death and prohibition, as well as procurement of the black vote, in order to assert legislative seats in the U.S. Congress, the state legislature, and the state executive office. The Mississippi Plan achieved these objectives and was eventually supported by South Carolina’s white Democratic constituency.

Freed blacks who suffered through pre-war slavery finally won their personal sovereignty. Under the law, it became their right to participate in elections as legal citizens. This transpired within the timeframe of the nation’s Reconstruction Era. As blacks quickly registered and crowded polling places, significant and nearly dramatic consequences occurred. In the 1874 election in Mississippi, the Republican Party won a 30,000-vote lead, taking over a gubernatorial territory that was a bastion of Democrats and had been firmly under their control. Republicans won the governorship, as well as a legislative majority of all seats that were up for the taking. Also, the election of black Republicans to numerous positions, including ten of the state legislature’s thirty-six members, rocketed momentum upwards for the GOP. This set the stage in 1874 for Democrats to begin conceptualizing their Mississippi Plan in the Southern state’s city of Vicksburg.

Armed Call to Arms and Politicized Violence

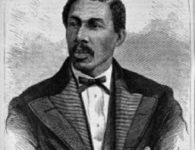

In Vicksburg, the so-called “White Man’s Party” dispatched members of a rogue and secret police force. These militant white bigots had plenty of firepower. They were feared by unarmed blacks and anyone who stood in their way. These secret police forces scared the state’s outgunned blacks to death. As a result, they sat out of the August 1875 election primary and stayed home. The Democrats saw their Mississippi plan coming to fruition. Every Republican municipal official was swept out of office during the August primary. By December, the emboldened party forced Crosby, Mississippi’s black sheriff of the state, to cut and run. Blacks arrived at Mississippi’s state capital to help Sheriff Crosby. However, they were met with the combined overwhelming force of the secret police and legions of angry white mobs — who also had firepower. According to many accounts from state historians, roughly 300 blacks, or more, were slaughtered in a bloody massacre, which went on for days after the failed election primary.

Hordes of angry whites then went into Vicksburg’s surrounding cities armed and ready–willing to shoot and kill any black woman, man, or child on sight. In the following January, President Ulysses S. Grant summoned a Calvary of U.S. Army fighters to Vicksburg to depose the uprising by white bandits and secure safety so that the black sheriff could return in peace. On June 7, 1875, the sheriff’s white deputy, A. Gilmer, had enough of having Crosby, a black man, as his boss. Fed up, Gilmer blew the law enforcement official’s head off. In 1875, the Democrats finally put their Mississippi Plan into action. They waged political war on two targeted battlefields. They wanted to destroy Republican morale. White paramilitary factions began to emerge, calling themselves the “military arm” of Democrats. Contrary to the tactics of the Ku Klux Klan (a racist terror group that was much more covert), the paramilitary forces wreaked sheer havoc right out in the open like no one was watching. Instead of burning crosses, they shot anyone standing in their way on sight.

Ballots and Bullets

The politically empowered bandits were treated like brave protectors of their communities. At times, the bandits sought out editors so they could be covered for their “valor.” The Red Shirts were the most feared of these paramilitary groups. Their empire stretched statewide and plenty of dangerous weapons were at their disposal. Privatized funding paid for their weapons and the funds flowed regularly. The more the money rolled in, the bigger their arsenal of weapons became. This is what gave them power and the ability to impose their will. The second part of the battlefield laid out in the Mississippi Plan was strictly about using the ballot as a weapon–not the bullet. Democrats wanted to talk 10% to 15% of Scalawags (white Republicans) into voting Democratic. Outright insults and threats of social, political, and economic marginalization caused candidates without any strong local ties to switch their party affiliation or abandon Mississippi. The Mississippi Plan’s stage two involved scaring black people out of their minds. Proprietors who rented living spaces, planters who owned land, and shopkeepers used financial stress to a limited extent against black sharecroppers.

However, the Red Shirts had absolutely no limits when it came to imposing their will and keeping the black population terrified. The so-called “rifle clubs” cause riots during Republican political rallies on a regular basis. Members of these clubs made sure black people were shot down by the hundreds like livestock during these organized political demonstrations. Although the governor sought Federal soldiers to quell the violence, President Ulysses S. Grant resisted acting for fear of being accused of “bayonet rule”—a charge he feared would definitely be utilized by Democrats to win Ohio’s state elections that year. Ultimately, the violence continued unabated, and the plot succeeded. At the close of the November 2, 1875, election in Mississippi, five counties with sizable black populations received 12, 7, 4, 2, and 0 ballots, respectively. In 1875, a Republican majority of 30,000 votes defeated a Republican majority of 30,000 votes in 1874. White Democrats’ triumph in Mississippi spurred the rise of the Red Shirts in North and South Carolina as well.

They were notably active in reducing black votes in South Carolina’s majority-black counties, where they are claimed to have perpetrated 150 killings in the weeks before the 1876 election.

References

“The Negro Sheriff Crosby…”. New York Times. June 8, 1875. http://query.nytimes.com/gst/abstract.html?res=9802E5D6153BEF34BC4053DFB066838E669FDE.

Ellem, Warren A. “The Overthrow of Reconstruction in Mississippi,” Journal of Mississippi History 1992 54(2): 175-201

Foner, Eric, Reconstruction: America’s Unfinished Revolution, 1863-1877. (1988).

Garner, James Wilford. Reconstruction in Mississippi (1901) online edition; full text online

Harris, William C. The Day of the Carpetbagger: Republican Reconstruction in Mississippi (1979) online edition

No comments