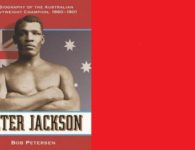

Photo credits: Twin Palms Publishers

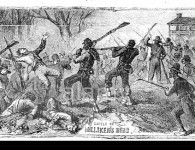

On April 14, 1906, just before midnight, two innocent Black men by the names of Horace Duncan and Fred Coker (aka Jim Copeland) were kidnapped from the county jailhouse and murdered in Springfield, Missouri by a frenzied white mob of several thousand members.

“Now the magnificent state of Missouri confronts the possible embarrassment of letting two innocent men be hung by a mob,” a newspaper stated two days after the public lynchings of Mr. Duncan and Mr. Coker.

A white lady claimed of being attacked by two African American males the day before the brutal lynching. Despite the fact that local police had “no proof against them,” Mr. Duncan and Mr. Coker were “arrested on suspicion.” Even though their employer had given an alibi to show that they were not engaged in the claimed attack, the men were brought to the county jailhouse to await trial.

During this time, it was race, not guilt, that rendered African Americans subject to indiscriminate suspicion and false accusations after a reported incident, even though there was no proof linking them to the claimed crime. The simple claim that a Black man had been sexually improper with a white lady sometimes resulted in violent retaliation before the court system could or would respond. According to one newspaper, the lynch mob in the case of Mr. Duncan and Mr. Coker “was focused on revenge and in no condition to discern between guilt and innocence.”

Even though the officers were armed and responsible for defending the individuals in their care, when the mob came to the county jailhouse to conduct its atrocity, local law enforcement did nothing to stop the enraged murderers from capturing Mr. Duncan and Mr. Coker. When the mob pulled Mr. Duncan and Mr. Coker outside, over 3,000 enraged white men, women, and children chanted, “Hang them!” and “Burn them!” The crowd in the public square hung both men from the Gottfried Tower’s balustrade, then ignited a fire underneath them — watching as their bodies were burnt to ashes inside the flames.

The mob returned to the prison and proceeded to lynch another African American man, Will Allen, as part of their spree of depravity. The local police had abandoned the inmates, and it was only until the state militia came that the crowd dispersed and stopped anybody else from escaping from the jail.

The lady who claimed being attacked gave a statement two days after the lynching of these three men, saying she was “certain” that [Mr. Coker and Mr. Duncan] “weren’t her attackers, and that she could identify her assailants if they were brought before her.” The lynch mob’s deed of racial terror, on the other hand, had left an indelible impression, scaring the whole Black community senseless.

To avoid the mob’s massacre, many local Black residents had fled their jobs and homes.

After the lynchings and mob violence, a grand jury was convened to indict anyone involved in the mob. Four white men had been arrested by April 19, and 25 warrants had been issued. Only one white man was brought to trial. However, no one has ever been found guilty.

According to the Equal Justice Initiative, Horace Duncan, Fred Coker, and Will Allen were three of at least 60 African American victims of racial terror lynching in Missouri between 1877 and 1950.

No comments