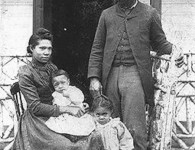

Photo credits: MormonWiki

Kwak Walker Lewis (pictured) was a 19th-century black abolitionist and barbershop owner.

Late in his life, Lewis was a disillusioned minister of the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints. He disassembled himself from the Utah state-based faith after he found out that it was merely another proponent of dogma founded on the myth of U.S.-styled white supremacy. Lewis also found that the Mormons chose to legalize slavery before he left.

Early Origins and Family Life

Lewis was born on August 3, 1798, in Barre, Worcester County, Massachusetts. His father, Peter P. Lewis, was a free black tenant landowner in Middlesex County, Massachusetts His mother, Minor Walker Lewis, was born a slave in Worcester County. Peter and his wife Minor had a total of eleven children. They were all born free and were members of Massachusetts’ black middle-class population.

Abolitionism was an important part of Walker Lewis’s family’s history. Kwaku Walker was his maternal uncle. Kwaku’s parents named him Kwaku, which means “boy born on Saturday” in a Ghanaian dialect. In Worcester County, Massachusetts, Kwaku, and his parents lived in slavery. But eventually, Kwaku won his release from Nathaniel Jennison, the white slavemaster who owned him, in two judicial trials.

Ties to the Legal Fights Against the Peculiar Institution

One of those trials was in 1781 and the other was in 1783. Legal precedents for abolishing slavery in Massachusetts include Kwaku v. Jennison (1781) and Jennison v. Caldwell et al (1783). In 1826, Walker Lewis co-founded the Massachusetts General Colored Association (MGCA) with this genealogy of slavery and freedom.

That same year, Lewis and other important black abolitionists, notably David Walker (not related), founded the MGCA, America’s first all-black abolitionist organization. Lewis and his allies also produced David Walker’s Appeal to the Coloured Citizens of the World in 1829.

This essay advocated for total freedom from slavery, starting a violent insurgency (if needed) to fight against slavery’s defenders, and strong opposition to African colonialism. The Massachusetts General Court Association eventually joined with William Lloyd Garrison’s New England Anti-Slavery Society (renamed The Boston Anti-Slavery Society).

Business Legacy and Alliance With the First Black Freemasons of the West

Walker Lewis, who specialized in children’s haircuts, had two thriving barbershops in the Massachusetts cities of Lowell and Boston by 1830. When he signed the 1827 Declaration of Independence from the Lodge of England with Prince Hall, Lewis helped to form the Grand African Lodge of Freemasons.

From 1829 until 1831, he was the grandmaster of Boston’s African Lodge. One branch of the Underground Railroad was constructed by Lewis and other immediate relatives. Walker Lewis converted to the faith of the LDS Church in 1843 by Parley P. Pratt. He was consecrated to the LDS priesthood in 1844 by William Smith, LDS leader Joseph Smith’s younger brother. Lewis was one of just two known black Mormon priests.

The other was Elijah Abel, who was ordained by Joseph Smith. Lewis moved to Utah Territory in late September 1851. He landed at Salt Lake City. Lewis returned to Lowell in October of 1852.

Lewis’ Discovery of Raging, Anti-Black Racism Combined With Religion

Lewis’ brief stint as a resident living in the state of Utah was marked by a shift in racial politics within the LDS church. Lewis obtained religious instruction in which church leaders made the revelation that he belonged to the Tribe of Canaan. This was theoretically the tribe reserved for black Mormons.

John Smith (uncle of Joseph Smith and patriarch of the LDS Church) is the religious leader who confirmed the alternative facts, which unveiled the revelation. Because of the mythical curse of Ham (the most dark-skinned son of the biblical prophet Noah), two church officials (Brigham Young and William Appleby) opposed the consecration of black Mormons.

The LDS bigots additionally opposed interracial marriages between black and white Mormons. They also knew that Lewis’s son had married a white Mormon woman in 1847. Young formulated these principles as primary pillars of the Mormon religion after becoming the church’s second president in 1847Inside Utah’s state lines, made enslaving African-Americans legal.

Utah Exodus and Final Years of Life

After feeling rejected by his adopted faith, as well as witnessing the truth about white racism in Utah, Lewis permanently ceased all involvement in the LDS Church upon returning to Lowell in 1852.

He died from complications from TB lung disease on October 26, 1856.

No comments