Flipboard has been used to gather some of the world’s greatest minds together to order to increase awareness, share information, and open our minds to knowledge not often seen throughout mainstream media.

In this Flipboard Find, we learn more about 1667: The year America was divided by race

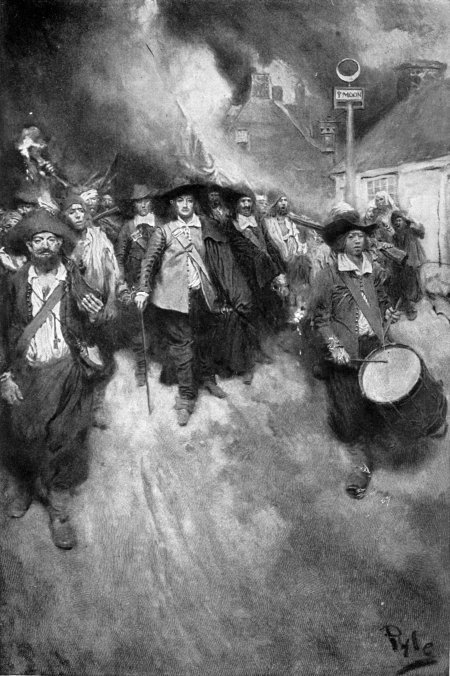

The Burning of Jamestown by Howard Pyle. It depicts the burning of Jamestown, Virginia during Bacon’s Rebellion (A.D. 1676-77); used to illustrate the article “Jamestown” in Harper’s Encyclopaedia of United States History: from 458 A.D. to 1905 (1905). Note the multi-ethnic composition of the painting. Source: Wikipedia

Genealogical research has sent me down an American history rabbit hole once again. I don’t mind. Being schooled on American history by genealogy is one of the reasons I Iove to do the research. It brings my ancestors’ lives to life. History provides the backdrop against which their lives were lived and provides a vital context.

So what if I were to tell you that blacks and whites in the American colonies lived together harmoniously? Even better…what if I were to tell you that whites and blacks saw each other as equals?

You’d think I was trying to sell you a mountain of pixie dust or a unicorn. Or telling you a bedtime story.

Nevertheless, it’s true. There was a time in this country’s history when black and white were united. Okay, to be precise, I’m going to have to come clean. I’m talking about poor whites: indentured European immigrants and European immigrants who had finished their term of servitude. I am also talking about free people of colour and enslaved people of colour.

This is the story of 2 American colonies: the one that existed before 1676 and the one that existed after 1676. So what’s so important about that year? Bacon’s Rebellion.

Bacon’s what? I hear you asking yourself. I know. I hadn’t heard of it either. It’s certainly nothing that was taught in school. Yet, it happened. I’d even go as far as to say that this rebellion defined America; more so than the American Revolution that would follow a century later.

I kept coming across references to Bacon’s Rebellion during some intensive 17th century era family research over the past few months. I was curious about it Was it a strange reference to some form of 17th Century acid reflux caused by excessive bacon eating? But in all seriousness, it was an episode in our country’s history that involved many of my ancestral lines. The sons of numerous family lines fought on both sides of this conflict. On the white side of my family tree, names like Ball, Berkeley, Byrd, Carter, Lewis, Mottrom, Page, Pugh, Randolph, Roane, Spottswood, Washington, and West figure largely within this conflict. All of them were resident in the Tidewater region of Virginia (Jamestown, Charles City County and Henrico County) at the onset of the rebellion. However, when I spotted names from the African-descended/mulatto lines of my tree – Christian, Cumbee/Cumbo, Drew, Goins/Gowen, and Thomas – I had to check it out. Like the white side of the family, these ancestors were also resident in Virginia’s Tidewater region.

Map of Virginia’s Tidewater region. Source: Virginia Department of Historic Resources

My ancestral links to this rebellion

My ancestors who were loyalists and adjudicators of the rebels:

Col. Augustine Warner – 1st Cousin

Major Robert Beverley – 2nd Cousin

Col. Mathew Kemp – 2nd Cousin

Col. William Claiborne – 1st Cousin

Col. Southy Littleton – 2nd Cousin

Lt. Col. John West – 1st Cousin

Major Law. Smith – cousin by marriage

Capt. Anthony Armistead – 1st Cousin

Ancestors who were part of the rebellion:

Henry West – 1st Cousin (banished from the colonies for 7 years)

John Sanders – 2nd Cousin (fined 2,000 lbs in tobacco)

Giles Bland – 2nd cousin (hanged)

William Hatcher – 1st Cousin (fined 8,000 lbs of pork , to be supplied to Virginia’s soldiers)

Sands Knowles – 2nd Cousin (Imprisonment and total forfeiture of all estates, lands, goods and slaves)

Henry Gee – Cousin by marriage (fined 1,000 lbs of pork)

Thomas Warr – 1st Cousin (banishment)

Col Henry Good – cousin by marriage (fined 6,000 lbs of pork)

And those who were a bit further down the colonial pecking order:

Henry Page – 1st Cousin (hanged)

William West – 1st cousin (hanged)

My curiosity was piqued. It was time to do some heavy reading.

A racial laissez faire among the lower classes in the American colonies

Before 1676, poor whites, blacks, and mulattoes worked side by side. They lived together and caroused together. And, they loved together. They recognised shared bonds of servitude and the sameness of their respective life situation. So much so that they even ran away together to escape their bonds of servitude. They established communities in the mountains and the wilderness areas of Virginia, far from the reach of the colonial Establishment. These men and women formed unions/marriages and blended.

Modern American DNA results via the major DNA testing services has proven this. Are you a white-identified American with trace amounts of African DNA? If your working class ancestors were in Virginia in the 17th Century, I offer the paragraph above as a partial-explanation. The same holds true for African Americans with trace amounts of European ancestry. The paragraph above is a partial explanation of how that may have happened within your ancestry.

There was no ‘racial purity’. That’s a modern myth. The Establishment certainly wanted to keep its bloodlines pure. Not even the poorest white could even dream of entering that world. Purity in the 17th Century Establishment’s mind was all about protecting its status, its privilege, its control, and its power. It’s the reason why the colonial elite only married other members of the elite. Racial purity as it’s espoused today? Sorry, it didn’t exist. It wasn’t even in its nascent stages. All of that would come in the latter part of the 18th Century. When there was serious money to be made from an artificial concept and an excuse to double down on slavery.

In his work entitled People’s History of the United States, historian Howard Zinn writes that 17th Century black and white servants were “remarkably unconcerned about the visible physical differences.”

Edmund Morgan, an important historian of colonial America, has this to say:

“There are hints that the two despised [by the colonial Establishment] groups initially saw each other as sharing the same predicament. It was common, for example, for servants and slaves to run away together, steal hogs together, get drunk together. It was not uncommon for them to make love together.”

And let’s not forget the Native Americans whose lands blacks and poor whites set up homes and communities within. They too married into this mix of black and white.

America was never a white nation. Don’t ever believe that it was. Not even for a millisecond. While I am focusing on the relationship between whites and blacks, 17th Century immigrants came from far and wide to the American colonies: Chinese, Jews, sub-Continental Indians, and Moors (Muslims from North Africa) were also here.

A colonial elite gripped by class fear and paranoia

The elite of colonial 17th Century Virginia was comprised of wealthy plantation owners, rich merchants, manufacturers, traders, their Burgesses (local government) and their governors. Yes, I know, quite a few of my British colonial ancestors were Establishment figures. Collectively, they were at the apex of colonial society. The colonial Establishment had two primary fears. The first was the hostile Indian population who controlled the nearby lands that surrounded the lands settled by European colonials. They also feared their indenture workforce and enslaved workforce. They had to contend with the class anger of poor whites – in other words, the property-less European immigrants – and the resentment of Africans who had been stolen from their homelands and trapped in a world as foreign to them as a trip to Mars would be for us.

Historian Edmund Morgan also wrote:

“Only one fear was greater than the fear of black rebellion in the new American colonies. That was the fear that discontented whites would join black slaves to overthrow the existing order.”

Just like the spice which had to flow on Arrakis in Frank Herbert’s Dune science-fiction novels…the cultivation of tobacco in Maryland and Virginia, the cultivation of rice in South Carolina and the production of cotton in the lower South had to continue. At any price. Tell you what, the next time you watch Dune (or read the books), substitute the words tobacco, rice and cotton every time the word ‘spice’ is mentioned…it’s a mind-bender. Herbert was so on point that it almost hurts.

The Establishment’s fear wasn’t entirely groundless either. Life in the early decades of the colonies was far from harmonious. There were quite a few instances of servants organizing rebellions. Resistance to the colonial status quo by the English, Irish, Scottish, and German poor can be seen in wholesale desertions and work rebellions. Work slowdowns were fairly common. There were strikes by coopers, butchers, bakers, porters, truckers, and carriers. And there was the other major dread of a hierarchy obsessed elite: mutinies at sea. Our colonial ancestors were an unruly and feisty bunch.

A colonial rebellion plot was recorded as early as 1663. The details of this plot show how white indentured servants and enslaved blacks plotted to rebel and gain their freedom. This plot was betrayed and all the conspirators were executed as an example.

The colonial Establishment in Virginia feared that class conflict would undermine their tobacco plantation holdings. My English ancestors in particular were perhaps most troubled by this. Between 1381 and 1549, four large peasant revolts played out in England. Each were the result of deep socio-economic and political tensions. The first rebellion, Wat Tyler’s Rebellion (1381), saw parts of London fall to the peasant army. The then king (a young Richard II) fled to the Tower of London where he took refuge. While this rebellion ultimately failed, its leaders meeting some pretty grisly ends, it scarred the psyche of the English ruling elite. The lower classes in England would never be entirely trusted again. Even to this day.

The Jack Cade Rebellion (1450) was the result of local grievances focused on the corruption and abuses of power by King Henry VI’s closest advisors. The rebels were incensed by the national debt that had been caused by years of warfare against the French, and the recent loss of the king’s Norman territory. Jack Cade led an army of men from Kent, to the south of London, and the surrounding counties. His army marched on London in order to force the government to end the corruption and remove the traitors surrounding the king’s person. Remember this revolt in particular. It’s comparison to Bacon’s Rebellion is almost a textbook case of history repeating itself.

The last English rebellion I’ll mention is Kett’s Rebellion (Norfolk, 1549). This too had a cause that is uncannily similar to Bacon’s Rebellion. Kett’s Rebellion was largely in response to the enclosure of land. Land was (and remains) a source of power in England. Privilege came with land. If you didn’t own land, you didn’t have a voice. Without a voice, you had no economic or political power.

When the lower classes united in England, they challenged the status quo, and the way in which power was centrally controlled. To counter-act any further uprisings, the English Establishment kept its poor on a back foot to ensure they wouldn’t pose a threat to its power.

As the younger sons and/or nephews of the British aristocracy and elite, Virginia’s colonial establishment would have been well versed on class warfare and the perils presented by a united lower class.

So let’s fast-forward 120 or so years and return to the lead-up to Bacon’s Rebellion.

The seeds of a rebellion

Map of Virginia at the time of Bacon’s Rebellion. Source: http://quotesgram.com

The colonial elite had a monopoly on the land. The best land, of course. Demand for the best land drove up the cost of acquisition. Which meant that poor whites and free people of color were forced to remove themselves into Native American territory to the west of the Tidewater region of Virginia. They were effectively cut off from any access to support from the colonial government. They were on their own. Which meant fending off Native American attacks on their own.

An additional grievance against the elite had to do with revenues. Fur trapping and fur trading with Native Americans was a monopoly controlled by Virginia’s elite. It’s a bit of a simplification, but true enough to say, that the colonial hierarchy controlled the when, where, and with whom the frontiersmen could engage in fur trapping and trading with. The two parties began to butt heads over this. It was another source of rising tension.

Classed as ‘rabble’, ‘the mob’, ‘uncouth animals’, etc, the colonial elite were relieved to see the back of this large underclass of people.

You can see where I’m going with this.

The colonial government used the situation to its advantage. They thought of these black and white Virginian frontiers people as an early defence system. If you think that’s me being cynical, that’s exactly what they were. And that’s exactly how they felt. They were human shields. Every attack on their farms and settlements led to a few of their number racing back to Jamestown to plead for soldiers to protect them and their families. Which, of course, alerted the colonial Government to Native American attack activity and where that activity was occurring. Of course the Establishment didn’t send any re-enforcements in the form of troops. It sent nothing.

Which, in turn, led to burning resentment for the frontiers people.

The snippet above made me think of the classic novel, The Last of the Mohicans. Okay…and the eponymous movie too. While the book takes place after Bacon’s Rebellion, the tensions between the elite and the frontiers people figures largely in the first part of the story. Remember the conversations between Hawkeye and John Cameron (whose farm is later attacked) where John recites his list of grievances against local government and the governor? The resentment between frontiers people and their government overlords still flamed brightly over a hundred years after Bacon’s Rebellion.

The Establishment’s worst fears came to fruition soon enough.

Nathaniel Bacon was a young member of the elite. Nevertheless, he formed a movement that was the Establishment’s worst nightmare. At first his movement was based on anti-Native American sentiment. It quickly evolved into an anti-aristocratic movement; a movement that came to symbolize the mass resentment of the poor against Virginia’s elite. Hundreds (some accounts claim up to a thousand) of white freedmen, white bond-servants, free people of colour, and enslaved blacks staged an armed insurrection against the Virginia colonial elite.

The rebellion ultimately led to the burning of Jamestown.

Engraver F.A.C. (signed lower right) of Whitney-Jocelyn, N.Y. – From p. 117 of Ilustrated School History of the United States and the Adjacent Parts of America. From a digital scan at the Internet Archive. Engraving captioned ‘The Burning of Jamestown’ showing the burning of Jamestown during Bacon’s Rebellion (1676). From Illustrated School History of the United States and the Adjacent Parts of America: from the Earliest Discoveries to the Present Time (1857). Source: Wikipedia

Garrisons and forts were taken by the rebels. Governor Council member Richard Lee (yet another ancestral cousin of mine) recorded that the rebellion had the overwhelming support of Virginia’s population. This support cut across class-lines, which must have been anathema to the Establishment.

So what was Bacon’s hope for the rebellion? A general “leveling”. In other words, the equalization of wealth, opportunity – and land.

Ultimately, despite its early successes, the rebellion failed. Nathaniel Bacon’s premature death from dysentery left a leadership vacuum which was filled by less capable men. The rebellion fell apart. The Establishment’s reprisals were swift and harsh. Some of the rebels who came from the working classes were executed. The elite who formed the rebellion’s leadership faced varying fates: deportation back to England to face trial, forfeiture of estates and land holdings, or stiff fines.

The suppression of the Bacon revolt was critical for the colonial rulers. Suppressing it would enable the ruling elite to (from Zinn):

1. develop an Indian policy which would divide Indians and pit them against one another;

2. underscore to poor whites that rebellion did not pay through a show of superior force (English troops and mass hangings);

3. develop a practice of dividing poor white immigrants;

4. drive a wedge between free people of color and enslaved blacks;

5. isolate people of colour and enslaved blacks from poor whites; and

6. develop a practice of dividing slaves based on occupation (field worker, skilled artisan/crafts person, house worker, etc) and complexion.

Bacon’s Rebellion was followed by a series of tobacco revolts. Once these smaller revolts were suppressed, the Establishment instigated a series of progroms to ensure social control. Front and centre were policies and codes that controlled poor whites and black servants, and slaves.

The Establishment learned from their English ancestors that the only way to survive, and maintain power and control, was the division of its common enemy. Developing a system of inequality between black and white servants, they could fashion the allegiance of the English poor to that of their masters.

This is the genesis of the slave codes that were passed in the decades after the rebellion. These slave codes codified the system of slavery. In doing so, the codes made the status of ‘slave’ a life sentence. It was a system that saved the worst penalties and punishments for blacks. This dichotomy in how people were treated, built an unequal structure of racial slavery where black labor were slaves while white laborers were not slaves, was bound to cause resentment amongst blacks with regards to the lighter punishments meted out to their former comrades and allies. It instilled a fear amongst the poor whites that they could suffer the same fate of harsh treatment that was meted out to blacks.

This was the beginnings of institutionalized racism: a system based on the unequal treatment of whites and blacks who shared very similar circumstances.

It did not end there. Once whites and blacks were divided, the next item on the agenda was dividing the non-English poor whites who largely came from Irish, Scottish and German backgrounds. The Establishment picked the Irish off first; re-igniting prejudices against them for their Catholicism. Anti-Irish propaganda portrayed them as unthinking brutes, animals, and rutting primates.

Both a reality and propaganda. Images like the one above were used to divide whites and blacks…and to depict the Irish as ‘not one of us’.

This approach was so successful that, once the Irish were isolated from other poor whites, the same memes were used against people of color. The wedge of religion and ‘foreignness’ was used to divide the Germans and the Scottish. Lutheranism and Calvinism were largely the religious denominations of the Germans. With preference being shown to Scottish Anglicism (The Church of Scotland), it was an effective wedge to use to split these two groups apart. The English began to treat the poor Scots in a manner like a wealthy cousin would treat a poor relation – with a thin and meagre kind of tolerance.

How effective was this practice of divide and conquer? Just tune in to CNN, Fox News, or MSNBC. Read a newspaper. Or look at the race memes that flood social media. Virginia’s colonial elite would be quite pleased to see the systems they put into play in the 17th Century didn’t merely survive – they have flourished. Take a look at how these memes have been adapted for every new immigrant culture that arrives on America’s shores.

Now I understand why Bacon’s Rebellion isn’t part of the history curriculum in the majority of America’s schools. I’ve counted only a meagre few that do cover this as part of their curriculum. No wonder most Americans have never heard of it.

Knowing what I know now, I have two fundamental questions. The first is what would America look like today had Nathaniel Bacon lived and succeeded in his aim? That question can’t be answered. I can see his vision, however.

The second is whether or not America can still achieve that vision, through non-violent means of course. In order for a nation of people to see that they have been played, in the most cynical and vicious way possible, they first have to recognize that they have been played. They have to grasp how they have been played, and why they have been played.

Then, and only then, can a system used to divide and conquer finally be dismantled.

Was your ancestor one of Bacon’s rebels?

While it isn’t a complete list of the rebels, this is the largest list of combatants that I have found online: Frazier, Kevin (2016). Bacon’s Rebels: A List of the Names and some of the Residences of the Rebel Participants in Bacon’s Rebellion of 1676 in Colonial Virginia, Rootsweb. http://freepages.genealogy.rootsweb.ancestry.com/~fraz/BaconsRebels

Sources

Allen, Theodore W. (1997). The Invention of the White Race, Vol. 2: The Origins of Racial Oppression in Anglo-America. London: Verso. https://books.google.com/books?id=OxwCQkCq4f0C&printsec=frontcover#v=onepage&q&f=false

Bacon’s Rebellion, Africans in America, Part 1, PBS. http://www.pbs.org/wgbh/aia/part1/1p274.html

Bailyn, Bernard. Politics and Social Structure in Virginia. Seventeenth-Century America. British National Archives: http://www.nationalarchives.gov.uk

Colonial State Papers, The British National Archives. http://colonial.chadwyck.com/marketing.do

Gardner, Andrew G. (2015). Nathaniel Bacon, Saint or Sinner?, Colonial Williamsburg Journal, Spring 2015. https://www.history.org/Foundation/journal/Spring15/bacon.cfm

Gormilie, Frank (2015). The Origins of Institutionalized Racism – a System to Control Blacks … and Whites, San Diego Free Press. (27 February 2015). http://sandiegofreepress.org/2015/02/the-origins-of-institutionalized-racism-a-system-to-control-blacks-and-whites

Library of Virginia. http://www.lva.virginia.gov/search.htm?cx=003101711403383086340:xhathpp67to&cof=FORID:11&q=bacon’s rebellion&sa=

Matthew, Thomas. The Beginning of Progress and Conclusion of Bacon’s Rebellion in the Years 1675 & 1676. Reprint Manuscript. P. Force, 1835. Original manuscript, 1675. http://memory.loc.gov/ammem/collections/jefferson_papers/tm.html

McCarter, William Matthew (2012). Homo Redneckus: On Being Not Qwhite in America, Algora Publishing.

Morgan, Edmund S. (1975). American Slavery, American Freedom: The Ordeal of Colonial Virginia. W.W. Norton & Company, Inc.

Rice, James D. (2012). Tales from a Revolution: Bacon’s Rebellion and the Transformation of Early America. Oxford University Press.

Rothbard, Murray N. (1979) Conceived in Liberty, Miles Institute. https://mises.org/library/conceived-liberty-2

Sainsbury, W. N. Virginia in 1676-77. Bacon’s Rebellion (Continued),

The Virginia Magazine of History and Biography. Vol. 21, No. 3 (Jul., 1913), pp. 234-248 https://www.jstor.org/stable/4243280?seq=1#page_scan_tab_contents

Salviati-Marambaud, Yvette. Nathaniel Bacon: A Frontrunner of the Revolution?. Vol. 19. Cycnos, 2008. http://revel.unice.fr/cycnos/?id=1268

Schilling, Vincent (2013). 6 Shocking Facts About Slavery, Natives and African Americans, Indian Country Today Media Network. http://indiancountrytodaymedianetwork.com/2013/10/09/5-little-known-facts-about-african-americans-natives-and-slavery-17th-century-151664

Tarter, Brent. (2011). Bacon’s Rebellion, the Grievances of the People, and the Political Culture of Seventeenth-Century Virginia, Virginia Magazine of History & Biography.

Thandeka (1998) The Whiting of Euro-Americans: A Divide and Conquer Strategy, World: The Journal of the Unitarian Universalist Association. Vol. XII No: 4 (July/August 1998), pp. 14 –20 https://msuweb.montclair.edu/~furrg/spl/thandekawhiting.html

Thompson, Peter. (2006). The Thief, the Householder, and the Commons: Languages of Class in Seventeenth-Century Virginia, William and Mary Quarterly. http://www.jstor.org/stable/3877353

Webb, Stephen Saunders (1995). 1676: The End of American Independence. Syracuse University Press. https://books.google.com/books?id=P1etgd8yjfkC&pg=PA87

Wyatt, David (2010). Secret Histories: Reading Twentieth-Century American Literature, JHU Press.

Zinn, Howard. (1997). A People’s History Of The United States. New York, NY: The New York Press.

No comments