By Bashir Muhammad Ptah Akinyele

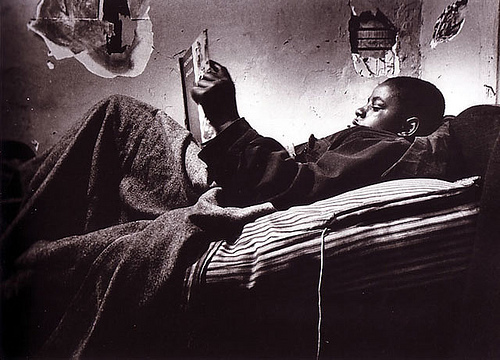

Photo credited to the author

“Out of all the cities I traveled to, Newark, NJ, was the only city where you heard people say “Hotep” in the streets.”

-A Community Activist in New Jersey

“Culture is a weapon in the face of our enemies”

—Amilcar Cabral (born September 12, 1924 – assassinated on January 20, 1973 by the Portuguese colonialists in Africa). He was a Bissau-Guinean and Cape Verdean agricultural engineer, pan-Africanist, intellectual, poet, theoretician, revolutionary, political organizer, nationalist, and diplomat. Cabral was one of Africa’s foremost anti-colonial leaders.

Recently, community activists and peace workers have been conducting aggressive anti-violence maneuvers in the streets of Newark, NJ. Outraged by the uptick in senseless community violence in the city in recent weeks, community activists and the city’s peace workers hosted a massive Stop The Violence March and Rally in the city of Newark on Thursday, July 21, 2022 and on July 28, 2022. Both rallies took place at 1:00 pm. The demonstrations were organized by Sharif Amenhotep of the Brick City Peace Collective and the Office of Violence Prevention and Trauma Recovery. The next scheduled anti-violence march and rally will start on South 20th Street and Springfield Avenue on August 4, 2022 at 1:00 pm.

However, Newark’s community activists and the city’s peace workers will leave South 20th Street and Springfield Avenue to march through the neighborhood to inspire the people to rally the community on South 19th Street and 19th Avenue against senseless community violence for peace. The efforts of the community activists and the city’s peace workers are to lead up to Mayor Ras J. Baraka’s massive city-wide peace walk, which is scheduled to take place on August 20, 2022 at 2:00 pm, starting from Chancellor Avenue and Aldine Street in the Weequachic section of Newark. I have joined the activists’ call for peace in the streets.

Unfortunately, I have lost over 46 students to senseless community in my years as a Newark Public School educator. One of the things we’ve been teaching and organizing our people about is the value of knowing oneself as a black person. The knowledge of ourselves gives us our direction, purpose, self-esteem, and pride. In the streets of Newark, the knowledge of self is finding its mission in our community and our people. And the word Hotep is the cultural impetus for the reawakening of the black mind.

For more information about Newark’s anti-violence and peace movements, click on the links below:

https://youtu.be/7a4U3VAY8C4

Medu Neter is the original African name for the hieroglyphics. The language of Medu Neter is the original written language of ancient Kemet. After the invasions and decimation of Kemet (Egypt) by the Europeans, they changed the word Medu Neter to hieroglyphics. Since the Arabs took over Kemet in 639 AD, the name “hieroglyphics” has been spread around the world by Europeans.

Kemet is a Medu-Neter word that means “land of the Blacks”. Kemet was a black civilization before the European and Arab conquerors. It is the greatest recorded civilization in the annals of human society on the planet Earth.

The name Kemet is the original name of Egypt. African Kemetic civilization and culture paved the way for today’s q, philosophy, architecture, religion, theology, monotheism, education, mathematics, astronomy, astrology, language, medicine, and government.

If you have never heard of the word “hotep,” it is an offer of peace. Some scholars argue that Hotep is the oldest written word for peace in human history.

In the 1980s and early 1990s, Afrocentricity became a major intellectual movement that engulfed the African world community. Under the Afrocentric movement, black scholars boldly challenged white supremacist views on African history and culture. One of the major scholars of the Afrocentric movement is Dr. Molefi Kete Asante. He is a professor of African American Studies at Temple University and the creator of the concept of Afrocentricity. He defines Afrocentricity in his book, “Afrocentricity,” as ” the centerpiece of human regeneration. To the degree that it is incorporated into the lives of millions of Africans on the continent and in the Diaspora, it will become revolutionary. It is purposeful, giving a true sense of destiny based upon the facts of history and experience. The psychology of African Americans without afrocentricity has become a matter of great concern. Instead of looking out from one’s own center, the non-Afrocentric person operates in a manner that is negatively predictable. The person’s images, symbols, lifestyles, and manners are contradictory and thereby destructive to personal and collective growth and development. ”

In an effort to inspire African people to reclaim our African mother tongue, African-centered scholars placed Hotep as a greeting and as a farewell benediction in the Afrocentric community. The word “Hotep” spread from the Afrocentric community to the world.

For more information on the media’s role in disparaging the word “Hotep” and Afrocentricity, please click on this link:

(https://patch.com/new-jersey/newarknj/damon-young-i-am-proud-hotep)

But on another level, Hotep opens our consciousness to the importance of knowing our own African history and culture. Why is this happening in Newark? For decades, we have taught our history and culture in the streets. Before Afrocentricity came on the scene, Kawaida made a huge impact on the black community in Newark in the late 1960s and early 1970s.

Kawaida’s best spokesperson and organizer was Imamu Amiri Baraka. Long before becoming the father of Newark’s current mayor, Ras J. Baraka, Amiri was born LeRoi Jones. He rose to prominence as a poet and writer.

He was one of the world’s greatest African American leaders for Black political power.

Amiri Baraka went on to become the father of the Black Arts Movement of the late 1960s and early 1970s. He inspired many intellectuals, poets and writers across America to teach Black pride in the African / African American community.

But many scholars, activists, and community leaders, argue that Imamu Amiri Baraka is also the real father of the movement for Black political power in America.

His embracement of Dr. Karenga’s philosophy of Kawaida and the principles of Kwanzaa inspired Father Baraka to mobilize masses of black people for political power. He taught many powerful lessons on the science of electoral politics from an African-centered perspective.

In 1967, Amiri Baraka organized the very first Black Power Conference in America in Newark, NJ. This conference took place after Newark experienced a massive African American rebellion against years of white racist violence and oppression. The white establishment calls black resistance to the centuries of racial discrimination in the city “the Newark Riots.”

The three-day Black Power Conference in Newark produced a Black Power Manifesto. It essentially said, “the colonialist and neo-colonialist control of Black communities in America and many Black nations across the world by white supremacists is necessarily detrimental and destructive to the attainment of Black Power.”

(https://riseupnewark.com/wp-content/uploads/2020/10/Black-Power-Manifesto-and-Resolutions-compressed.pdf)

He went on to organize a second Black Power conference and a Black and Puerto Rican convention in the city.

In 1972, Amiri Baraka co-convened the National Black Political Convention in Gary, Indiana. This convention is credited with increasing the number of black elected officials in America since US Reconstruction.

That same year, Father Baraka organized masses of black people to politically challenge white supremacy in the city of Newark. His efforts helped to elect Ken Gibson, its first black mayor, and elected a myriad of African American councilpersons to city hall.

Baraka’s wisdom demonstrated to black people how to acquire, organize, and seize political power under the Kawaida philosophy and the principles of Kwanzaa. And one of the biggest lessons Baraka taught, by example, was organizing through “unity without uniformity,” manifesting itself under Umoja. The first principle of Kwanzaa is called Umoja (Kiswahili for unity).

To read more about Afrocentricity and Kawaida, read this link:

(https://patch.com/new-jersey/newarknj/kawaida-afrikan-centricity-foundations-blackness)

Afrocentrism in Newark influenced my life and my educational pedagogy. As a long-time history and Africana Studies teacher in the city of Newark, I have greeted my students with Hotep for 28 years in the classroom. Saying Hotep not only keeps the peace in school, it also opens my students’ curiosity to their desire to know more about the role black people played in the development of human religions and civilizations.

In the spirit of Afrocentricity, my students greet me with Hotep anywhere and everywhere I go in the Newark area with a black power fist. Some of them have been inspired to learn more about our great history and culture. Some of my students have been drawn to our anti-violence rallies because they heard the word Hotep being cried out loudly from the microphone at our anti-violence rallies in the middle of the intersections and at our peace walks in the city.

In Summation

To de-escalate violent conflicts among Black people, we must now struggle to separate Hotep and our history and culture from our everyday philosophical way of life. If we don’t, our blood will continue to be spilled in our community due to senseless community violence in America and the world.

Peace!

Hotep!

–Bashir Muhammad Ptah Akinyele is a history and African studies teacher at Weequahic High School in Newark, New Jersey. He is also the co-coordinator for ASCAC’s (the Association for the Study of Classical African Civilizations) Study Group Chapter in Newark (https://(ascac.org/) and Nation of Gods and Earths (https://(ascac.org/)

No comments