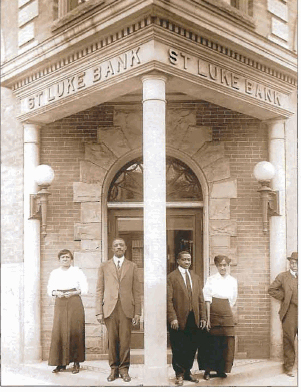

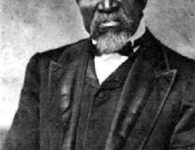

Born in 1867 in Richmond, Va., Walker started the St. Luke Penny Savings Bank in 1903 with $9,430 in deposits gathered from members of the Independent Order of St. Luke, an African-American benevolent society. The order had been formed after the Civil War to take care of the sick and cover funeral expenses of members in exchange for small monthly dues.

Since girlhood, Walker had been active in the order. At the turn of the century, when she became its executive secretary, its membership began to dwindle. Walker reinvigorated the institution, building its national membership to 100,000.

In the process, she found that white-owned banks did not want to take deposits from a #black organization, says Vernard W. Henley, chairman and chief executive officer of Consolidated Bank & Trust Co., the current name of the bank she started. White bankers’ reluctance gave her the idea to start a bank, which would be the order’s financial arm. “Let us put our moneys together; let us put our money out at usury among ourselves, and reap the benefit ourselves,” Walker said in a 1901 speech to the group. “Let us have a bank that will take the nickels and turn them into dollars.”

Two years later, St. Luke Penny Savings Bank was formed, with Walker as its president. By 1913, assets had grown to over $300,000, and she presided over the flourishing black community of Jackson Ward in Richmond, sometimes called the Harlem of the South. It was home to five other black-owned banks and scores of other African-American-owned businesses. “She made loans to black businesses, she made loans to students, she made loans to people to buy houses,” says historian Muriel Branch, co-author of the biography, Pennies to Dollars: The Story of Maggie Lena Walker. Walker also set up a weekly newspaper, the St. Luke Herald, which she edited, and a department store that ultimately failed after the white community boycotted it and its suppliers.

While many of the largest black-owned banks went under during the Great Depression, Walker’s bank survived, in part by merging with two smaller, black-owned banks in 1930, when it was renamed Consolidated Bank & Trust. Today, Consolidated has assets of $116 million, and the majority of its shareholders, who include two of Walker’s descendants, are African Americans. “I think what she had in mind was that African Americans ought to help themselves, and they ought to provide the opportunities for employment and development,” says Henley, who adds that her philosophy is one the bank still upholds.

By Jeremy Quittner in New York

[email protected]

article found @http://www.businessweek.com/smallbiz/news/coladvice/reallife/rl990706r.htm

No comments