Reginald Francis Lewis was born in Baltimore, Maryland, on December 7, 1942. Lewis’ father was Clinton Lewis, a small business owner, and his mother was Carolyn Cooper, a teacher. After their divorce, Cooper remarried a local postal worker, Jean Fugett, Sr.

The young Reginald Lewis showed a penchant for entrepreneurial endeavors early in life. By age nine, Lewis began selling newspapers within his Baltimore community, earning $20 a week in the early 1950s. According to the inflation calculator at the Bureau of Labor Statistics, that is the equivalent of about $200 a week — no small amount for the times and for a young man his age.

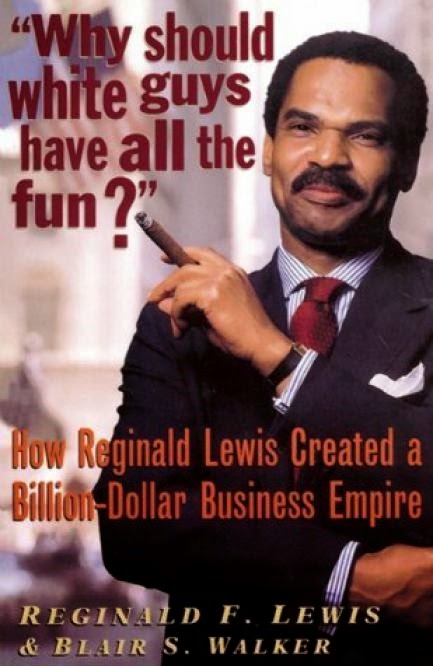

Lewis loved sports. A quarterback on the local football team, he won a football scholarship to HBCU Virginia State College in Petersburg, Virginia. In 1965, he graduated with a B.A. in Economics. In his autobiography, Why Should White Guys Have All the Fun?, he admits that despite having made the best grades at Virginia State, he decided he wanted to go to law school. His law school acceptance is the kind of story from which legends are made, worthy of retelling.

In essence, without a formal application to Harvard Law, Lewis traveled to the school and convinced the university’s administration to admit him. After a visit to the campus, his legendary charisma won over the school’s decision makers. He was told to submit the application later. It was a good investment for Harvard Law School. In fact, Lewis would donate $3 million dollars to the school in 1992 — making him the then-largest individual donor in the school’s history.

By 1968, Lewis had graduated from Harvard Law School and was headed to New York City. He soon began working as a lawyer at Paul Weiss Rifkind Wharton and Garrison. By the early 1970s, he had opened his own law firm, Lewis and Clarkson. The law partnership specialized in venture capital projects.

By the 1980s, Reginald Lewis’ legal and business acumen in venture capital projects translated over to corporate takeovers. He would leave the practice of law to pursue business ventures full time. This change in career direction would eventually earn him a distinction as the richest African American man in the 1980s.

Through a $23 million buyout, Lewis had acquired McCall Pattern Company, a well respected dress-pattern firm. He sold the company four years later, in 1987, for $63 million. With only $1 million of his own money invested in the original takeover, his profit from the sell was $50 million, reported by the New York Times.

Lewis acquired The Beatrice Companies in 1987, a foods company with large operations in Europe. This deal cost him $985 million dollars. He formed all of his food business concerns under the umbrella of TLC Beatrice International, with TLC standing for The Lewis Company. At the time, it was the largest firm run by a person of African descent. The global conglomerates under his operations included 64 companies that operated in 31 countries. Food interests ranged from an ice cream-making company in Germany to a sausage production house in Spain.

It was a great investment for Lewis. TLC Beatrice would make Fortune’s 500 list with a valuation of $1.5 billion. However, Lewis’ autobiography illustrates that his successes were not without challenges. For example, in 1991, when he attempted to take TLC Beatrice Foods public through a stock offering, the market was not receptive.

Before his death on January 19, 1993, at the young age of only 50 years, Lewis had donated millions of dollars to various institutions, from churches to homeless shelters. The Abyssinian Baptist Church and Kappa Alpha Psi Fraternity were both large recipients of his philanthropy. He also donated to the HBCUs Virginia State College and Howard University.

He knew he had a tumor for about two months before he died, said Rev. Jesse Jackson, a close friend to Lewis. “He spent the last two months preparing for treatment,” said Jackson, “and getting his whole house in order, in terms of the company and his family.”

Lewis was survived by his wife, Loida Lewis, and two daughters, Christina and Leslie. His transition plan including leaving the running of his companies substantially to his half-brother, Jean S. Fugett, also a trained lawyer.

Lewis’ name will certainly be remembered for generations to come. In Baltimore, to keep this great legacy alive, there are the Reginald F. Lewis Museum of African American History and Culture and the Reginald F. Lewis School of Business and Law High School were constructed. Harvard University constructed The Reginald F. Lewis International Law Center at the university’s campus and also offers the Reginald F. Lewis Fellowship for the teaching of Law.

5 Comments

So glad to hear the man’s works will be passed on to inspire others. How many have not been lionized by the people

in the communities in which they served? His accomplishments were amazing and there should be books and movies

about them for ALL to read and see!

I agree, Mr. Tippett. Everyone needs to know who this man was!

Viagra Effetto Collaterale Precio Cialis 4 Comprimidos Amoxicillin Side Effects Drowsiness Best Buy Doxycycline

Clomid Date Regles Productos Para Una Ereccion Mas Larga Is Amoxicillin For Women Only cialis Proscar O Propecia Tablette Levitra

I read his book. He’s been a major inspiration to me for years. I’m always telling the young people I come I. Contact with. About the legendary man of color. His story should begin the big screen. Hope to see the history maker there soon.