On March 3, 1991, Rodney G. King was pulled over and beaten mercilessly by Los Angeles Police Department officers Stacey Koon, Laurence Powell, Theodore Briseno and Timothy Wind. The incident was recorded by witness George Holliday from the balcony of his apartment using the then new camcorder technology and replayed thousands of times on television news stations across the country. The trial went on for months, and on April 29, 1992, “Sgt. Stacey C. Koon and Officers Laurence M. Powell, Theodore J. Briseno and Timothy E. Wind are acquitted of the March 3, 1991, beating of Rodney G. King. Jurors were not convinced that a 81-second videotape of the incident represented the entire story.” This decision was received with righteous outrage by the masses of black people concentrated in South Central Los Angeles, especially in light of the March 16, 1991 shooting of Latasha Harlins, 15, by a Korean grocer named Soon Ja-Du. Harlins allegedly attempted to steal a bottle of orange juice from Soon’s store, and subsequently was shot in the back of the head.

Immediately after the verdict was announced, protesters outside the police headquarters in Downtown Los Angeles assumed a militant stance, engaging in running street battles and skirmishes with the police. In South-Central Los Angeles, the focal point of the 1965 Watts Riots, protesters gathered at the intersection of Florence and Normandie Avenues and engaged in a struggle with the police and threw rocks and bottles at passing vehicles. White truck driver Reginald Denny was pulled from his vehicle and beaten to near death, his head smashed open with a concrete block. His ability to speak and conduct basic tasks was impaired for life. The police retreated and didn’t return for almost three hours. Fires were set and expropriation of property from nearby stores began. Firefighters responding to the scene were fired upon. Fidel Lopez, a Guatemalan immigrant and construction worker, was also attacked near Florence and Normandie roughly an hour after Denny, $2,000 being stolen and his head being smashed with a car stereo. Downtown continued to be a scene of struggle as well, with vehicles being owned by city administrators and the wealthy being smashed to pieces by militants.

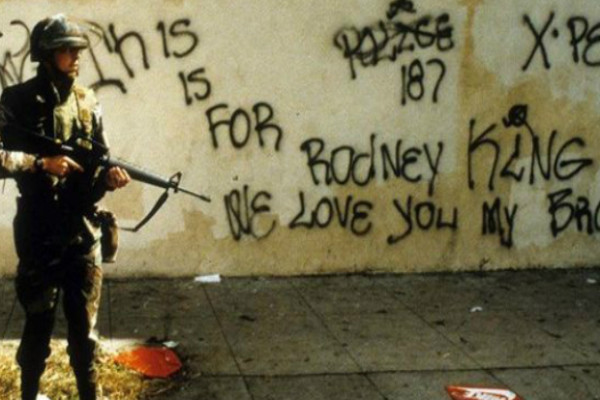

Mayor Ed Bradley called a state of emergency at 8:45 on the evening of the 29th, after joining with others in condemning the beating, saying that the “system failed us…The jury’s verdict will never blind us to what we saw on that videotape. The men who beat Rodney King do not deserve to wear the uniform of the L.A.P.D.” Governor Pete Wilson mobilized 2,000 National Guard troops and ordered them to Los Angeles.

On the morning of the 30th, the City of Los Angeles saw transit service suspended, a curfew covering a wide swath of the city in place, schools closed, and restrictions on the sale of gasoline and ammunition in place. The National Guard was in the streets by noon, and at 12:45 PM a citywide curfew was ordered by Mayor Bradley. Korean merchants, many of whose buildings were targeted by militants who remembered the Harlins murder, organized self-defense militias and prepared to shoot/kill “looters” and “arsonists”. This strained relations between the Black/Brown and Korean communities for years. On May 1, troops from the Marine Corps and Army arrive at bases in preparation for deployment to put down further unrest. By May 4, the brunt of the violence was over and residents began to return to work and school.

President George H.W. Bush declared the city of Los Angeles a disaster area. 63 people were killed, 2,116 people were injured, 9,400 people were arrested, 4,500 fires were set, and one billion dollars of damage was done.

Rebellions also took place in several other cities, including Las Vegas, Nevada.

No comments