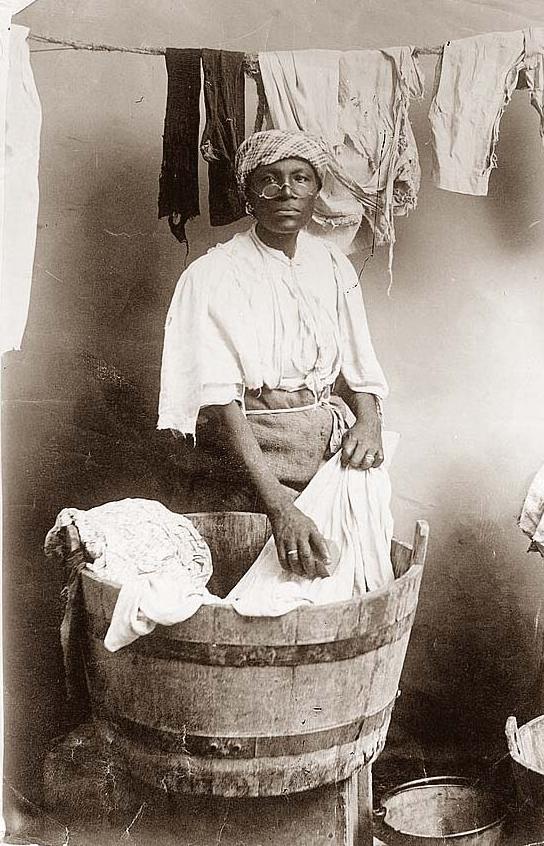

An article by the father of black history, Carter G. Woodson about the sacrifices of the Negro washerwoman.

The Negroes of this country keenly resent any such thing as the mention of the Plantation Black Mammy, so dear to the hearts of those who believe in the traditions of the Old South. Such a reminder of that low status of the race in the social order of the slave regime is considered a gross insult. There is in the life of the Negro, however, a vanishing figure whose name every one should mention with veneration. She was the all but beast of burden of the aristocratic slave-holder, and in freedom she continued at this hard labor as a bread winner of the family. This is the Negro washerwoman.

This towering personage in the life of the Negro cannot be appreciated today for the reason that her task is almost done. Because of the rise of the race from drudgery and the mechanization of the industrial world the washerwoman is rapidly passing out. Confusing those women employed in laundries with those washing at homes, the Bureau of the Census in 1890 reported 151,540 washerwomen, 218,227 in 1900, and 373,819 in 1910. In 1920, however, there were actually 283,557, but this number has comparatively declined.1

Through machinery and the division of labor the steam laundry has made the washing of clothes a well organized business with which the toiler over the wash tub cannot compete. The price required for this laundry service is not always lower than the charges of the washerwoman, but the modern laundry offers so many other conveniences and advantages that the people are turning away from her to the new agency. Only the most unfortunate and the most inefficient washerwoman who is unable to do anything else and must work for the lowest wages remains to underbid or obviate the necessity for introducing the steam laundry system. The Negro washerwoman of the antebellum and the reconstruction periods, then, has passed from the stage. For her, however, an ever grateful people will have a pleasant memory, and generations unborn may honor her in brass and stone.

And why should the Negro washerwoman be thus considered? Because she gave her life as a sacrifice for others. Whether as a slave or a free woman of color of the antebellum period or as a worker in the ranks of an emancipated people, her life without exception was one of unrelenting toil for those whom she loved. In the history of no people has her example been paralleled, in no other figure in the Negro group can be found a type measuring up to the level of this philanthropic spirit in unselfish service.

The details of the story are interesting. When a slave she arose with the crowing of the fowl to sweat all but blood in the employ of a despotic mistress for whose household she had to toil often until late in the night. On return home she had to tax her body further to clean a neglected hut, to prepare the meals and wash the clothes of her abandoned children, while her husband, also worn out with the heavier burdens of the day, had time to rest. In addition to this, she often took in other work by which she saved sufficient money to purchase her freedom and sometimes that of her husband and children. Often she had compassion on a persecuted slave and used such savings to secure his liberation at a high cost only to let him go free for a nominal charge.2

As a slave, too, the washerwoman was the head of the family. Her husband was sometimes an uncertain quantity in the equation. Not allowed to wed according to law, they soon experienced that marriage meant living with another with the consent of the owners concerned and often against the will of the slaves themselves. Masters ordered women to take up with men and vice versa to produce numerous slave offspring for sale. When the slave hesitated because of the absence of real love the master’s will prevailed. Just as such matches were made according to the will of the master they were likewise broken by the selling of the man or the woman thus attached, and in the final analysis the care of the children fell to the mother while the father went to the bed of another wife on some remote plantation.3

To provide for her home the comforts which the custom of slavery did not allow she had to plan wisely and work incessantly. If the mother had not developed sufficiently in domestic art to earn a little money at leisure she usually fell back on “taking in washing.”4 When free during the antebellum period the drudgery of the Negro washerwoman was not much diminished. The earning power of her husband was not great since slave labor impoverished free labor, and the wife often had to do something to supplement the income of her unprofitable husband. Laboring, too, for those who were not fortunately enough circumstanced to have slaves to serve them, the free Negro woman could earn only such wages as were paid to menial workers. In thus eking out an existence, however, the washerwoman was an important factor. Without her valuable contribution the family under such conditions could not have been maintained.5 In the North during these antebellum times, the Negro washerwoman had to bear still heavier burdens.

In the South, her efforts were largely supplementary; but, in the North, she was often the sole wage earner of the family even when she had an able-bodied husband. The trouble was not due to his laziness but to the fact that Negro men in the North were often forced to a life of idleness. Travelers of a century ago often saw these black men sitting around loafing and noted this as an evidence of the shiftlessness of the Negro race, but they did not see the Negro washer-woman toiling in the homes and did not take time to find out why these Negro men were not gainfully employed. Negro men who had followed trades in the South were barred therefrom by trade unions in the North,6 and the more enlightened and efficiently trained Irish and Germans immigrating into the United States drove them out of menial positions.7

In many of the Northern cities, then, Negro men and children were fed and clothed with the earnings of the wife or mother who held her own in competition with others. In most of these cases the man felt that his task was done when he drew the water, cut the wood, built the fires went after the clothes, and returned them. Fortunate was the Northern Negro man who could find acceptance in such a woman’s home. Still more fortunate was the boy or girl who had a robust mother with that devotion which impelled her to give her life for the happiness of the less fortunate members of an indigent group. Without the washerwoman many antebellum Negroes would have either starved in that section or they would have been forced by indigent circumstances to return to slavery in the South, as some few had to do during the critical years of the decade just before the Civil War.8

The Negro washerwoman, too, was not only a breadwinner but the important factor in the home. If the family owned the home her earnings figured in the purchase of it. When the taxes were paid she had to make her contribution, and the expenses for repairs often could not be met without recourse to her earnings. When the husband could not supply or showed indifference to the comforts of the home it was she who replaced worn out furniture and unattractive decorations and kept the home as nearly as possible according to the standards of modern times. She could be depended upon to clean the yard, to decorate the front with flowers, and to give things the aspect of a civilized life. In fact, this working woman was often the central figure of the family and the actual representative of the home. Friends and strangers calling on business usually asked for the mother inasmuch as the father was not always an important factor in the family.9

This same washerwoman was no less significant in the life of the community. The uplift worker sought her at home to interest her in neglected humanity, the abolitionist found her a ready listener to the story of her oppressed brethren in chains, the colonizationist stopped to have her persuade the family to try life anew in Liberia, and the preacher paid his usual calls to connect her more vitally with the effort to relieve the church of pecuniary embarrassment. While burdened with the responsibility of maintaining a family she was not too busy to listen to these messages and did not consider herself too poor to contribute to the relief of those who with a tale of woe convinced her that they were less favorably circumstanced than she. Oftentimes she felt that she was being deceived, but she had rather assist the undeserving than to turn a deaf ear to one who was actually in need.10

The emancipation of the Negroes as a result of the Civil War did not immediately elevate the status of the Negro washerwomen nor did it bring them immediate relief from the many burdens which they had borne. In their new freedom certain favorably circumstanced Negroes were disposed to assume a haughty attitude toward these workers. After emancipation Negro men rapidly withdrew their wives and daughters from field work and restricted their efforts largely to the home; but the washerwomen who went out occasionally to do day work or had the clothes brought home, remained for several generations. There was yet so much more for them to do in the reconstruction of a landless and illiterate class that the importance of this role could not be underrated. For a number of years thereafter, then, certainly until 1900 or 1910 there was little change in the part which these women played in the economic life of the Negro.11

Why should the Negro washerwoman have to continue her unrelenting toil even after emancipation? This makes an interesting story. In the first place, the Negro was nominally free only. The old relation of master and slave was merely modified to be that of landlord and tenant in the lower South. The wage system established itself in the upper South, but soon broke down in certain parts because there was no money with which to pay; and the tenant system which followed with most of the evils of slavery kept the Negro in poverty.

With such a little earning power under this system it was a godsend to the Negro man to have a wife to supplement his earnings at some such labor as washing. She did not always receive money for her services, but food and cast-off clothing and shoes contributed equally as much to the comfort of her loved ones. White employers and black employees were all hard put to it while the South was trying to recover from its devastation and the whole country was undergoing a new development, but one class could help the other, and both managed in some way to live.12

In the course of time, too, when the problem of eking out an existence had been solved there came to the ambitious program of the freedmen other demands which made the services of the Negro washerwoman indispensable. In the first place, the freedmen were urged to buy homes, and they could easily see the advantage of living under one’s own vine and fig tree and of thus forming a permanent attachment to the community. Land was cheap, but money was scarce. To make such a purchase and at the same time carry the other burdens did not permit the withdrawal of the washerwoman from her arduous task. Often she was the one who took the initiative in the buying of the home, for the husband did not always willingly assume additional responsibilities.13

Then when the home had been purchased the children had to be educated. Negroes were ambitious to see their children in possession of the culture long since observed among the whites; and they were urged by the missionary teachers from the North to seek education which, as a handmaiden of religion, would quickly solve their problems. This often meant the education of the whole family at once; for, since the indifference and the impoverished condition of the South rendered thorough education at public expense practically impossible, the washerwoman had to come to the front again to bear more than her share of the burden. The missionary schools established by teachers from the North required the payment of tuition as well as board and room rent. Many things now supplied to students free of charge, moreover, had to be purchased in those days by their parents.14

Sometimes, too, when there were no children to educate, the husband was ambitious to become a teacher or minister, and he had to go to school to qualify for the new sphere. The wife usually took over the responsibility of the home which she often financed through the wash tub. The Negro teacher or minister who did not receive such support in obtaining his education was an exception to the rule. Without this particular sacrifice of the washerwoman the Negro professional groups would be far less undermanned than what they are today. Many of the prominent Negro teachers, ministers, business men, and professional workers refer today with pardonable pride to sisters, mothers, and wives who thus made their careers possible.15

In not a few cases the earnings of the Negro washer-woman went to supplement that of her husband as capital in starting business enterprises. This effort today is not easily estimated because most of such enterprises never succeeded. For lack of experience and judgment these pioneers in a hitherto forbidden field soon ran upon the rocks, and the highly prized savings of their companions together with their own accumulations sank beneath the wave only to discourage a people who had to grope in the dark to find the way. As a rule, however, the woman bore her losses like a heroine in a great crisis, being the last to utter a word of censure or to despair of finding some solution of a difficult problem. Often when the man at his extremity was inclined to give up the fight it was his courageous companion who brought a word of cheer and urged the procession ouward.16

In cooperative business, this worker was a still larger factor. The Negro washerwoman, continuing just as she had been before the Civil War in social uplift and religious effort, served also in the capacity of a stockholder in the larger corporations of Negroes. Being already the main support of the school and church, she could easily become interested in business. At the same time the Negro teachers and professional classes, who in being taught solely the superiority of the other races had developed an inferiority complex, could not have confidence in the initiative and enterprise of the uneducated Negroes who launched these enterprises.

The Negro working women who had not been misguided by such theories had no such misgivings. The only thing they wanted to know was whether it was something to give employment, prestige, and opportunity for leadership. They believed in the possibilities of their own group and willingly cooperated with any one who had a high sounding program. They were not the ignorant and the gullible, but the true and tried coworkers in the rehabilitation of the race along economic lines.17

Some of the leading enterprises like the St. Lukes Bank in Richmond, the North Carolina Mutual Life Insurance Company of Durham, and the National Benefit Life Insurance Company of Washington still count among their stockholders noble women of this type. These businesses have developed to the point that the well-to-do and educated Negroes now regard them as assets and participate in their development, but the first dimes and nickels with which these enterprises were launched came largely from women of this working class.

C. G. WOODSON

1U.S. Bureau of the Census, Negro Population in the United States, 1790 to 1915, p.526; Fourteenth Census of the United States, Vol. V, p.359.

2 Woodson, Free Negro Owners of Slaves in the United States in 1830, p. VI

3 Journal of Negro History, XIV, p.236-237.

4 This was always a possible resort because this sort of work was looked upon as too menial for the whites.

5 To appreciate how washerwomen figured in the life of the Negroes see Williams, History of the Negro Race in America, II, 136

6 During the thirties and forties the trades unions barring Negroes were beginning to make themselves felt.

7 Woodson, A Century of Negro Migration, pp.41, 82.

8 Some of the Northern States had laws barring Negroes who were not self-supporting. See Hickok, The Negro in Ohio, pp. 41, 42; and Harris, Negro Servitude in Illinois, pp. 10, 24, 121, 138, 148, 157, 162, 233-236

9 Certain fathers, however, were equally as conspicuous. See Journal of Negro History, XIV, 239.

10 Church workers, understanding this weakness of the Negro women, have exploited them as a class known to he generous to a fault.

11 The United States’ Census figures are confusing because at one time launderers and laundresses in and outside of laundries are reported together, but in other cases they are separate.

12 Many poor whites of that day were not any better off than the Negroes, but they were too proud to work.

13 Biographical treatments in the Journal of Negro History, passim; and data in questionnaires filled out for the Association for the Study of Negro Life and History.

14 Because of rapidly diminishing income the missionary schools are not as well equipped as they were in those days, and public institutions better equipped are taking their places.

15 Data in the files of the Association for the Study of Negro Life and History

16 Dabney, Maggie L. Walker, passim; Andrews, John Merrick, passim; and The Modern Jack and the Beanstalk, passim.

17 The Negro as a Business Man, p. 90 et seq

Source: The Journal of Negro History, Vol. XV, July 1930, No. 3

No comments