Photo credits: The Florida Today/The Florida Historical Society

Adults in Jacksonville, Florida’s Laura Street Presbyterian Church asked the young president of the NAACP Youth Council 60 years ago if he and other youths still wanted to demonstrate inside two downtown department stores at all-white lunch counters.

The sit-in demonstrations had started Aug. 13. Protesters had been kicked, spit at, and were the targets of racial slurs. On August 27, 1960, a crowd of white men, some from the Ku Klux Klan, held ax handles and baseball bats as they gathered in Hemming Park.

But the whole day was about to become violent, with 50 people injured and 62 arrested.

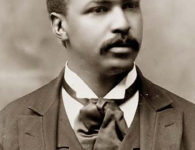

Speaking to the Florida Tines-Union newspaper, witness Rodney Hurst recalled the events of Ax Handle Saturday, the day when he escaped a bat and ax-wielding mob of whites determined to break up lunch counter sit-ins near Hemming Park.

“At the time, we did not measure whether or not what we were going to do or what we did would cost us,” said Rodney Hurst, who was the youth council president at 16.

He said the students were on a mission and would have disobeyed their elders if directed to remain in the church. Ax Handle Saturday was the most tumultuous moment in Jacksonville’s efforts to integrate.

In commemoration, the NAACP, the National Conference for Community and Justice, the Jacksonville Historical Society, the Human Rights Commission, and the Jacksonville Urban League hosted a series of events in the year 2000.

Laura D’Alisera, NCCJ executive director, said she wants all Jacksonville residents to attend the ceremonies to learn the history, gain insight, and to show how far the city has come in 40 years.

Ax Handle Saturday symbolized a wake-up call in Jacksonville’s civil rights movement for many residents who either were unaware or hid from the changes at hand.

“I think this was really the first time that Jacksonville in a very serious way faced the fact that blacks — who were about 45 percent of the population then — were unhappy with the way things were,” said Spence Perry, 58, who lives in Hagerstown, Md., and witnessed the riot as a college student.

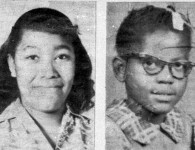

Weeks after the massacre, white and black committees started meeting to discuss how to integrate the city’s private and public establishments. In April 1961, Hurst and the NAACP’s youth council secretary Marjorie Meeks ate lunch for a week at Woolworth’s white counter to prepare segregationists for the evolution of integration.

When the Civil Rights Act of 1964 passed, the laws were changed about separate water fountains, bathrooms, and stores for the races.

“That [Ax Handle Saturday] shows what happens when white folk and black folk don’t talk. It also forced this community to own up to some of the racial problems it was having,” Hurst said.

He recalled that members of the youth council left Laura Street Presbyterian in groups of twos and threes that morning. About 30 headed to the W.T. Grant store on Main Street and another group went to Woolworth’s on Hogan Street.

Hurst and others bought items at Grant’s to show the business would take their money at the register. However, once the students sat at the lunch counter for white clients, the workers placed closed signs on the counter. The overhead lights went out and the salt and pepper were slid away.

For about 10 minutes protesters waited until they were satisfied Grant’s would not reopen for lunch that day and the day’s business earnings were gouged. Hurst said a group of white men swooped toward the black students as they exited the store.

Hurst ran and was eventually picked up by an adult member of the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People.

Meanwhile, a few blocks away in Woolworth’s a group accompanying a 24-year-old Alton Yates, vice president of the youth council, sat down at the white lunch counter.

“We got the usual runaround from the waitresses. Some of them taunted the kids to get them to do something foolish,” Yates said.

That lunch counter was closed, too. But Yates and the others stayed, until the action outside heated up.

“We were trying to get kids out of the store when our attackers came in,” said Yates, who was hit in the head while pushing his way out.

Members of the black gang called the Boomerangs swooped in as a buffer between the fleeing students and the white mob of about 200.

“We were out there trying to save a community,” said Perry Raines, a Boomerang member. “Everybody had to run; if you didn’t, you wouldn’t live.”

Students sought the white Memorial Church at Monroe and Laura streets, less than a block away, as a safe haven, but to Yates, it seemed like a mile. They couldn’t go the shortest distance through Hemming Park (now Hemming Plaza) because that’s where blacks were being brutally beaten.

“I really did not think adults would attack children with baseball bats and ax handles. That was particularly unreal to me. It was a horrific thing to watch,” said Yates, pointing out that some protesters were as young as 13.

Perry said seeing the violence in a peaceful place was jarring.

“Seeing this idyllic green square, a very peaceful kind of context, seeing it dissolve almost into a battleground, was disturbing,” he said.

Several sources said police, some of whom were at the scene, did not intervene in the melee. A Florida sheriff named Nat Glover, who was 17 at the time, later told the Times-Union in 1999 he was not involved in the demonstration.

However, he walked from his job at Morrison’s cafeteria into the angry crowd on his way home. Glover was struck on the shoulder and then on the head.

Source: Alliniece T. Andino and the Florida Times-Union

No comments