Editor: Danielle A. Jackson

Photo credits: Wea/Rhino/Getty Images

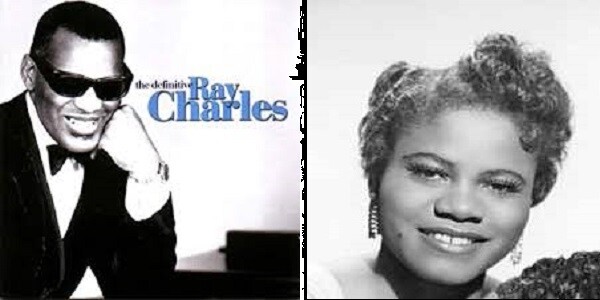

The voice of Margie Hendrix (pictured right) on “Night Time is The Right Time” comes at you out of nowhere, like an explosive, thunderous crack in the sky after a period of steady rain.

Long after the song is over, it’s her words that stay ringing in your ear. You’ll belt out, “Babyyyyyyy!” in the shower, while out for a jog, or when giving your friends a hard time as they share their most trying relationship conundrum. On The Cosby Show, it’s her part that is most memorable when reenacted by adorable, pig-tailed Rudy, played by Keshia Knight Pulliam.

In the 2004 biopic Ray, it was future Academy Award winner Regina King who played the role of Hendrix. King spoke of the difficulty in channeling the musician, as few references, visual or text, were available to use as inspiration for the role.

“There isn’t a lot of information out there on Margie, so I had to rely on her voice to guide me,” King said.

The kind to stop you in your tracks, Hendrix’s voice remained unchanging, and from her earliest solo releases to her final years, it was an infallible offering from an artist who was moved to sing.

I stared at a blank page for days trying to figure out how best to begin my story on Hendrix, but nothing felt appropriate, fitting enough for the woman who had outsung Ray Charles. I’ve thought about her regularly for years, wondering how a woman with that voice could disappear from the public eye so easily, after making such an unforgettable appearance.

It’s a thought that’s stayed with me because it carries the sobering reality that someone can be incredibly talented — phenomenal even — and still find themselves omitted by history. It could happen to anybody, but it seems to happen most often to talented Black women who are bold enough to chase their dreams, then fall apart from the sheer pressure of it all. Women who are public but invisible and who are noticed without really being seen. Women like Margie Hendrix.

She was born in Georgia either in 1935 or 1939, in the tiny town of Register, Bulloch County — the nearby city of Statesboro had a population 5,000 — during the height of the Great Migration. She had an older sister, Lula, and a brother, Harley, who passed away when Margie was just a toddler.

Starting from the early part of the 20th century until the mid-1970s, the Southern United States saw an exodus of African-Americans moving to the Northwest, Midwest, and Northeastern parts of the country. For many, economic disenfranchisement had made upward mobility impossible, and poor housing along with low-quality education ensured they remained at a social and structural disadvantage.

Another reason for this mass movement from the South, one more terrifying and pernicious, was the constant fear of lynching at the hands of white mobs.

Hendrix didn’t look like the performers most record producers wanted Black women to be. She was too dark, had a gap between her two front teeth and was a Southern girl with none of that Northern polish and glam. The music industry of today is incredibly corrosive and toxic, but it was even more so for Black musicians in the middle of the twentieth century, who dealt with nothing but no-good managers, unfair contracts, and stolen music credits.

Anti-black racism and its social realities make it astounding that artists emerged who weathered through even when it seemed like everyone at some point or another crumbled, with many never making it back. The argument could be made that had Hendrix managed to stay far from the drugs that would ravage her body, and kicked those bad habits, she would have lasted longer and achieved success rivaling that of her still living peers from that “golden” era.

Yet the number of Black women uncounted and unnamed in music history makes it clear that this wasn’t only a question of sobriety. It was also about opportunity and a perverse lack of care for the artists whose mental and physical health were secondary so long as money continued to be made. Hendrix’s death and eventual erasure from the mainstream were not simply tragic turns in a complicated life.

That unfortunate double-whammy was also the outcome of a series of events that befell a woman unloved by those she committed herself to and unprotected by those whose coffers she filled.

Hive is a series about women and the music that has influenced them, edited by Danielle A. Jackson. Read more at Longreads and The Believer. This story was originally titled A Lover’s Blues: The Unforgettable of Margie Hendrix

No comments