When the Continental Congress delivered a 1777 decree for the 13 colonies to give thanks for a victory over the British at Saratoga, African-Americans took part in the regional celebrations, continuing in what had become a familiar custom of rejoicing for bountiful harvests and drought-breaking rains.

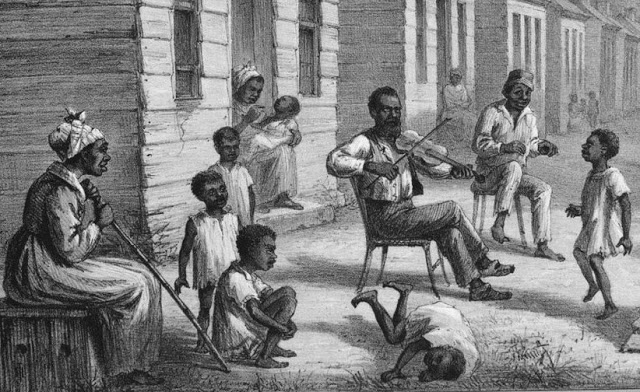

Field slaves caught wild game often accompanied by a serving of cornmeal while house slaves dined on leftovers from the “big house” after the slave-owners family finished their own feasts.

Similar to the Puritan practice of setting aside times for fasting and giving thanks, for many African-Americans, any notion of Thanksgiving existed alongside the Christian faith.

“In the context of the African-American community, Thanksgiving was certainly a church oriented celebration,” African-American studies professor Dr. Crenshaw Dailey told theGrio.

“And one that had a kind of communal impulse in the sense of people gathering with the church as the epicenter.”

As some would say, Thanksgiving was about church.

Thanksgiving Day sermons could be heard throughout black churches in Antebellum America as pastors gave voice to the fears, struggles, hopes and triumphs of a people who were still a commodity in an increasingly powerful nation. Many of these sermons openly mourned the institution of slavery, the suffering of the black people and pleaded for the collective awakening of a slave-free consciousness in America.

Hosea Easton’s 1828 Thanksgiving Day Address to blacks in Rhode Island was nothing short of a dynamic diatribe against slavery and racism. In the speech, the multi-ethnic prominent abolitionist called for a “racial uplift” of the black race in America.

African Methodist Episcopalian cleric, Reverend Benjamin Arnett stirred a predominantly black congregation on November 30, 1876 with Biblically inspired words:

”…we call on all American citizens to love their country, and look not on the sins of the past, but arming ourselves for the conflict of the future, girding ourselves in the habiliments of Righteousness, march forth with the courage of a Numidian lion and with the confidence of a Roman Gladiator, and meet the demands of the age, and satisfy the duties of the hour…”

“Then let the grand Centennial Thanksgiving song be heard and sung in every house of God; and in every home may thanksgiving sounds be heard, for our race has been emancipated, enfranchised and are now educating, and have the gospel preached to them.”

The often-perceived conundrum of black slaves in colonial America giving thanks has baffled many, but perhaps justification and just maybe validation became more tangible after the U.S. Congress outlawed the importation of slaves into the U.S. and its territories on January 1, 1808.

But the ceasing of the buying of imported African slaves in America did not end what is sometimes referred to as America’s original sin, the institution of slavery.

It continued for more than half a century later.

1 Comment

[…] post Even During Slavery, Black Americans Always Found Reason To Give Thanks appeared first on Black […]