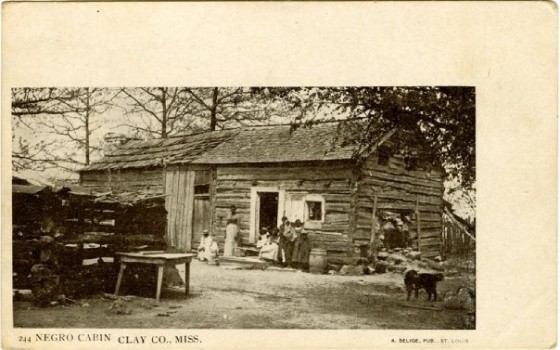

County: Clay

From the WPA Slave Narratives:

Jim Allen age 87

“Yas mam, I members lots about slavery time, case I was ole enough.

I was bawned in Russell County, AL, and can tell you bout my own mudder and pappy and sisters and brothers.

Mammies name was Darkis and her Marster was John Bussey, a regular old drunkard, and my pappies name was John Robertson and belonged to Dr. Robertson a big farmer on Tombigbee river five miles east of Columbus. De Dr. heself, lived in Columbus.

My sister Harriet and brother John was fine field hands and Marster kep em in field most of time, trying to dodge other white folks. (I believe he meant to keep from selling or paying debts with them).

Den der was Sister Vici and bruder George. Befo I could member much, I members Lee King had a saloon close to Bob Allen’s store in Russell County, AL, and Mars John Bussey drunk my Mudder up. I means by dat, Lee King took her and my brudder George for a whiskey debt. Yes old Marster drinked em up. Den dey was carried to Florida by Sam Oneal, and George was jest a baby. You know de white folks wouldn’t ofen separate the mother and baby. I aint seen em since.

Did I work? Yes Mam, me and a girl worked in de field carrying one row, you know it took two chillerns to make one hand.

Did we have good eatins? Yes Mam. Ole Marster fed me so good for I was his pet. He never lowed no one to pester me neither. Now dis Marster was Bob Allen who had took me for a whiskey debt, too. Mars Bussey couldn’t pay, and so Mars Allen took me a little boy out of the yard where I was playin marbles. De law lowed the first thing the man saw, he could take.

I served Mars Bob Allen ’till Gen. Grant come along and had me and some others to follow him to Mississippi. We was in de woods hidin de mules and a fine mare. Dis was after emancipation, and Gen. Grant was comin to Mississippi to tell de niggers dey was free.

As I done tole you, I was Mars Allen’s’ pet nigger boy. I was called a “stray”. I slep on de floor by ole Miss and Mars Bob. I could a slep on de trundle bed, but it was so easy jist to roll over and blow dem ashes and make dat fire burn.

Ole Miss was so good, I’d do anything for her. She was so good and weighed around 200 pounds. She was Mars Bob’s second wife. Nobody posed on me, No, Sir! I carried water to Mars Bob’s store close by and he would allus give me candy by de double hands full, and as many juice harps as I wanted. De best thing I ever did eat was dat candy. Marster was good to his only stray nigger boy.

Slave niggers didn’t fare with no gardens ‘cept the big garden up at the big house, when field hands was called to work out hers.

All de niggers had a sight of good things to eat from dat garden and smoke house.

I kin see old Lady Sally now cookin for us niggers, and Ruth cooked in white folks kitchen. Ruth and old Man Pleas and old lady Susan was gin to Mars Bob when he married and come to Sandford, AL

No, dere wasn’t no jails, but a guard house. When niggers did wrong dey was oftin sent there, but most allus dey was jest whipped when too lazy to work and when day would steal.

Our clothes was all wove and made on de plantation. Our everyday ones we called “hickory stripes”. We had a plenty and good uns. We was fitted out and out each season, and had two pairs of shoes, and all de snuff and tobacco we wanted each month.

No, not any weddins. It was kinder this way. Dere was a good nigger man and a good nigger woman, and the Marster would say, “I knows you both good niggers and I want you to be man and wife dis year and raise little niggers, den I won’t have to buy dem.”

Marse Bob lived in a big white house with six rooms. He had a court house and a block where he hired out niggers, jest like mules and cows.

How many slaves did us have? Les see!

Dere was old lady Sally and her six chillern and old Jake, her husband, de ox driver for de boss. Den dere was old man William and Cindy, the field hands and three children. Den dere was old man Starling, Rose, his wife and four chillern, some of dem was mixed blood by de over seer. I sees em right now. I knowed de over seer was nothin but po white trash, jes a tramp. Den dere was me and Katherin. Old lady Sally cooked for de overseers, seven miles away from de big house.

Everybody was waked up at four o’clock by a bugle blowed mostly by a nigger, and was at dere work by sun up. den de quit at sunset.

I shos seed bad niggers whipped as many times as dere is leaves on dat ground. Not Mars Bob’s niggers but our neighbors. We was called “free”, case Mars Bob treated us so good.

The whipping was done by the overseer or driver, who would say as he put the whip to the back, “Pray sir, pray sir!”

I seed slaves sold oftner dan you got fingers and toes, you know I tole you dere was a selling block close to our store. Den plinty niggers had to be chained to a tree or post because he would run away and wouldn’t work.

Dey would track de run aways with dogs and sometimes a white scalawag or slacker would be caught doggin duty. I seed as many deserters as I see corn stalks over in dat field. Dey would hide out in day time and steal at night.

No I didn’t learn to read and write but my folks teached me to be honest and mind old Miss and granny. Dey didn’t want us to learn how to go to de free country.

We had a neighborhood church and bof black and white went to it.

Dere was a white preacher and sometimes a nigger preacher would sit in de pulpit wid him.

The slaves set on one side of the isle and white folks on de other. I allus liked preacher Williams Odem, and his brother Daniel De slidin elder. De come from Ohio, Mars Bob Allen was head steward. I members lots of my favorite songs. Some of dem was, “Am I Born to Die”, “Alas and Did My Savior Bleed”, “Must I to de Judgment be Brought”. The preacher would say, “Pull down de line and let the spirit be a witness, working for faith in de future from on high.”

I seed de patarollers every week. If de niggers didn’t get a pass in hand write from one plantation to anoder, dem patarollers would get you.

Dey would be six and twelve in a drove, and dey would get you if you didn’t have dat piece of paper. No sun could go down on a pass. Dere was no trouble between niggers den.

We lay down and rest at night in de week time. Niggers in slavery time riz up in de quarter, could hear em for miles. Den the corn-shuckins took place. Den we would have singing. When one found a red ear of corn, dey would take a drink of whiskey from the jug and cup. We’d get through about ten o’clock. The men didn’t care if dey worked all night, for we had the “Heavenly Banner’s” (women and whiskey) by us.

Some time we worked on Saturday afternoon, owin to de crops, but women all knocked off on Saturday afternoon. On Saturday nights we mostly had fun, playing and drinking whiskey and beer, no time to fool around in de week time.

Some went to church and some went fishing on Sunday. On Christmas “we had a time – all kinds eatin, women got new dresses, men tobacco, had stuff to last until Summer. Niggers had good times in most ways in Slavery time. July 4th we would wash up and have a good time. We hallowed dat day wid de white folks. Dere was a barbacue – big table set down in bottoms. Dere was niggers strolling around like ants – we was havin a time now. White folks too. When a slave died, there was a to do over dat. Hollering and singing. More fuss dan a little. “Well, sich a one has passed out and we gwine to de grave to tend de funeral we will talk about Sister Sallie.” De niggers would be jumpin as high as a cow or mule.

A song we used to sing was “Come on Chariot and Take Her Home, take Her Home

Here come Chariot, les ride,

Come on Les ride.

Come on Les ride.”

Yes we believed hants would be at de grave yard. I didn’t pay no tention to em do, for I know de evil spirit is here, if you don’t believe it, let one of em slap you. I aint seed one but I’ve heard em.

I seed someone, dey said was a ghost – but it got away quick.

When we got sick de Dr. come at once, and Mistess was right there to see we was cared for. A Dr. lived on our place. If you grunt he was right dere. We had Castor oil and pills and turpentine and quenine when needful and herbs were used. I can find that stuff now what we used when I was a boy.

Some of us wore brass rings on our fingers to keep off croup. Realy good. Good now. See mine?

Yea, I know all about when yankees come. Dey got us out of de swamp. I was layin down by a white oak tree sleep, and when I waked up and looked up and saw nothin but blue,

blue, I said “yonder is my Boss’ fine male horse, Alfred. He tended dat horse himself.” He took it to heart, and he didn’t live long after de Blue Coats took Alfred.

Peace was declared to us 1st. Jan. in Alabama, but not in Mississippi until Grant come back May 8th.

I aint seen my boss since dem Yankees took me away. I was seven miles down in swamp when I was took.

I wouldn’t er told him good bye. I jist wouldn’t lef him, no sir I couldn’t have left my good boss. He told me dem Yankees was coming to take me off. I never wanted to see him case I would have gone back for he ‘tected me and loved me.

Like dis week, I lef the crowd one day Capt. Bob McDaniel came by, and asked me if I wanted to make fires and work around de house.

I said I’d like to see de town where you want me to go and den I come to West Point, it wasn’t nothin but cotton rows – lot ole shabby shanties, with just one brick store, and it belonged to Ben Robertson, and I hope (helped) build all stores in West Point since den.

I seed de Ku Klux. We would be workin. Dose people would be in de field, and must get home before dark and shet de door. Dey wore three cornered white hats with de eyes way up high. Dey skeered de breeches off of me. First ones I got entangled wid was right down here by cemetery. Dey just wanted to scare you. Night riders was de same thing. I was one of de fellers what broke em up.

Ole man Toleson was de head leader of de negroes. Trying to get negroes to go against our white people. I spec he was a two faced Yankee or carpet bagger.

We had clubs all around West Point –

Capt. Shattuck out about Palo Alto said to us niggers one day “Stop your foolishness – go live among your white folks and behave. Have sense and be good citizens.” His advise was good and we soon broke up our clubs.

I aint been to no school ‘cept Sunday School since srender. A good white man I worked with, taught me enough to spell “comprestibility and compastibility.” I had good remembrance and I could have learned, white folks jest taught me and dey sees dey manners in me.

I married when I was turning 19 and my wife 15. I married at big Methodist Church in Needmore. Same old church is dar now. I hoped build it in 1865. Aunt Emaline Robertson and Vencent Petty, and Van McCanley started a school in N.E. part of town two years after war.

Emaline was Mr. Ben Robertson’s cook, and her daughter Callie was his housekeeper, and Geo., and Walter, was mechanics. Geo. became a School teacher.

Abraham Lincoln worked by ‘pinions of de Bible. He got his meanings from the Bible. “Every man should live under his own vine and fig tree”. Dis was Abraham’s ‘mandments. Dis is where Lincoln started – “No one should work for another.”

Jefferson Davis wanted po man to work for rich man. He was wrong in one ‘pinion, and right in other. He tried to take care of his nation. In one instance Lincoln was destroying us.

I joined the church to do better and to be with Christians and serve Christ. Dis I learned by association and harmonius living with black and white, old and young and to give justice to all.

De fust work I did after de war was for Mr. Bob McDaniel who lived near Waverly on Tombigbee river. Yes Mam, I knowed de Lees’, and de Joiners out on de river den and long after and worked for dem lots in Clay County.

Interviewer notes:

(Jim Allen, West Point, age 87, lives in a shack furnished by the city. With him lives his second wife, a much older woman. Both he and his wife have a reputation for being “queer” and do not welcome outside visitors. However, he readily gave an interview and seemed most willing to relate the story of his life.

This interview was made, while sitting under the shade of a fig tree in the yard of the old negro.

The shack in which he lives is furnished him by the City. Such has been the case for a number of years. It can scarcely be called a shelter for the rain and winds have full sway, as well as sunshine, flies and mosquitoes.

With the old man, lives his second wife, a much younger woman. The neighbor negroes scarcely knew them and it was difficult to find their names. I wanted to do so before contacting them. I was told that they were “queer”, and didn’t want any one to come about them. However, my approach was easily made, and interview most agreeable and informative. I wish I had the gift of dialect so others could by reading this, see and learn of this fast vanishing type of the negro race. Around the almost fallen down shack, is corn and a few vegetables which they feebly cultivate. Most unique windbreaks are thrown up on all sides by all kinds of debris being pilled up.

They claim to be getting $2.00 from relief and a can of beef now and then.

When asked why the wife didn’t cook the cabbage, he said they were not any good without grease. Since the interview they have had grease (meat) meal coffee and sugar sent to them.

With shame I learned that he has been a most useful negro man. His two children seem very neglectful – true to form.)

Interviewed by: Mrs. Ed Joiner

Transcribed by Ann Allen Geoghegan

Mississippi Narratives

Prepared by

The Federal Writer’s Project of

The Works Progress Administration

For the State of Mississippi

The WPA Slave Narratives are interviews with ex-slaves conducted from 1936 through 1938 by the Federal Writers’ Project (FWP), a unit of the Works Progress Administration (WPA). Both the FWP and its parent organization, the WPA, were New Deal relief agencies designed by the administration of President Franklin D. Roosevelt to provide jobs for unemployed workers during the Great Depression.

The WPA Slave Narratives consist of 3,500 relatively brief oral histories (most of them two- to four-pages long), representing about 2 percent of all ex-slaves surviving in the late 1930s. The sample for Mississippi was somewhat smaller: out of perhaps 20,000 living former slaves, 450 were interviewed by the WPA. All states and territories that had slaves in 1865 are represented, except Louisiana which did not participate.

1 Comment

Reading the Slave narratives is really the ONLY way to learn what slavery was like in those times from the people who lived it. Much other “History” from 1860-1875 is highly politicized by one side or the other and was written usually by white politicians with an agenda to promote or someone to exploit. One needs to read many of these stories, and from several different states, to get a good idea about what slavery was really like. It seems that the more WEST one went, the slaves were less tightly controlled. In Louisiana many had their own accounts at stores and even purchased their own ammunition for hunting. Many had their own gardens and sold produce at the market. In the EAST, however the rules were more strict. they were more confined to the plantation. All in all the Beatings, etc. DID happen, only not as much as the historians would have you believe—most of the times it was threats that were never carried out—or happened on “some other Plantation” and never their own.