Photo credits: The Elephant/C.J. Lee

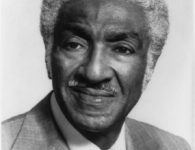

Frantz Fanon was a psychoanalyst who used both his clinical research and lived experience of being a black man in a racist world to analyze the effects of racism on individuals –particularly on people of color- and of the economic and psychological impacts of imperialism.

Fanon is an important thinker within postcolonial and decolonial thought whose work has had a widespread influence across the social sciences and humanities. Like many canonical postcolonial thinkers, Fanon’s personal biography is often viewed as important in understanding his published work. Fanon was born on July 20 in the French colony of Martinique in 1925. He studied at the Lycée Schoelcher in Fort-de-France, where he was taught by writer and poet Aimé Césaire.

Fanon was involved in supporting the French resistance against the Vichy regime in the Caribbean, and against the Nazis in France (though he experienced daily racism while serving in the army). After the Second World War, he went to study medicine and psychiatry in Lyon. Following his studies, Fanon became involved in struggles against colonialism under the influence of African freedom fighters who went to France to garner support for their struggles. In 1953 he went to Algiers as head of the psychiatric department at the Bilda-Joinville Hospital.

In Algeria Fanon was appalled by the difference in living standards between the European colonizers and the indigenous population, and by the racism experienced by the Algerians.

The 1954 Algerian revolt was met with a violent response involving torture, repression, physical abuse and widespread killings of Algerians by the colonisers. This served to radicalise Fanon and he supported the revolutionaries in secret for two years before resigning from his job at the hospital in 1956 and joining the National Liberation Front. He moved to Tunis, founded the Moudjahid (Freedom Fighter) magazine, and became a leading ideologue of the Algerian revolution.

He traveled widely in Africa to speak on his anti-colonial ideas and was ambassador to Ghana for a period. Though Fanon was from the Antilles, following his experiences in Algeria he came to think of himself as Algerian. He died of leukemia in 1961. Fanon’s key works are Black Skins White Masks, A Dying Colonialism, The Wretched of the Earth, and Toward the African Revolution. Black Skins White Masks was published in 1952 but did not gain widespread recognition until the late 1960s.

This was one of the first books to analyze the psychology of colonialism. In it, Fanon examines how the colonizer internalizes colonialism and its attendant ideologies, and how colonized peoples, in turn, internalize the idea of their own inferiority and ultimately come to emulate their oppressors. Racism here functions as a controlling mechanism, which maintains colonial relations as ‘natural’ occurrences. Black Skins White Masks is written in an urgent, fluid style.

It is both analytical and passionate, part academic text, part polemic. The book has provided a powerful and lasting indictment of racism and imperialism.

A Dying Colonialism is a historical document. It is a firsthand account of the Algerian revolution, describing how the Algerian people became a revolutionary force, and ultimately were successful in repelling the French colonial government. It is also, however, a philosophical discussion of the meaning of the conflict and what might come after it. Toward the African Revolution is a collection of articles, essays, and letters which spans the period between Black Skin, White Masks and The Wretched of the Earth.

The Wretched of the Earth was published just before Fanon’s death, very much with the Algerian independence struggle in mind. Prefaced by Jean-Paul Sartre, the book offers a social-psychological analysis of colonialism, continuing his argument that there is a deep connection between colonialism and the mind, and equally between colonial war and mental disease. In The Wretched of the Earth Fanon argued for violent revolution against colonial control, ending in socialism.

These struggles must be combined, he argued with rebuilding a national culture, and in that sense, Fanon was a supporter of socialist nationalism.

In The Wretched of the Earth, Fanon not only writes about violence in the international context, colonialism, national consciousness, and freedom fighting, but he also includes a psychoanalytic investigation of mental disorders associated with colonial war. The book, then, continues his work of drawing connections between the inner world of subjugated individuals and the workings of international politics.

This is something that has been continued by other scholars in the postcolonial tradition including Ashis Nandy and Ngugi wa Thiongo.

Source: Submitted by Lucy Mayblin to GlobalSocialTheory.org

No comments