Photo credits: Photo Researchers

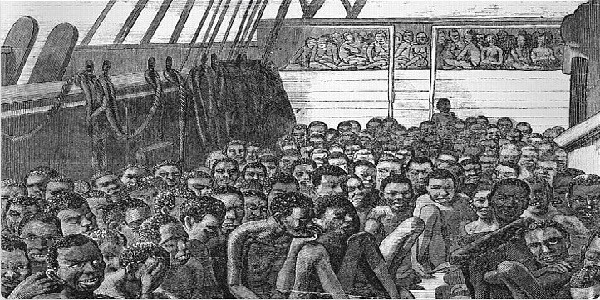

On July 8, 1860, the slave ship Clotilde landed at Mobile, Alabama, well over 50 years after Congress outlawed the importation of enslaved Africans.

More than 100 West African slaves were on board the ship. The Clotilde’s captain, William Foster, was eventually identified as working for white Mobile shipyard proprietor Timothy Meaher. Captain Foster moved the captive Africans to a riverboat, set fire to it, and then sank the Clotilde in order to avoid being apprehended by federal agents. The party of white men that funded the journey afterward divided up the Africans that had been transported as slaves. On Magazine Point, his plantation to the north of Mobile, Alabama, Meaher housed over 30 Africans.

Cudjo Lewis, a man who later went by the name of Cudjo, was one of the Africans. When the Civil War broke out in 1861, Meaher and his collaborators became accused of smuggling Africans into the nation illegally. However, a federal court rejected the prosecution. Real African men and women were at the center of the case, which was never the subject of any inquiry or resolution. During the pendency of the government’s litigation, Meaher said the Africans that were still on his land deserted on their own and were given no way of traveling back to Ghana.

The Clotilde survivors that Meaher had previously kept captive were free in 1865, following the end of the Civil War and the widespread abolition of slavery, but they were still stranded in a foreign country distant from their home. They established a village that was fashioned after the customs and government they had to flee, around the edges of Meaher’s property, in a location that became known as “Africatown.”

The residents of Africatown had a direct, current link to their African heritage and strong recollections of their culture, language, and rituals, in contrast to the great majority of newly liberated Black people in the nation who had presumably been born in the U.S. or taken from Africa decades earlier. The progeny of the Clotilde inhabitants who lived in Africatown preserved their distinctive language and culture of survival far into the 1950s.

The final survivor of the Clotilde passengers in Africatown was Cudjo Lewis. Zora Neale Hurston, a Black anthropologist, and author visited Alabama in 1927 to interview Mr. Lewis about his life and publish a book that details it. Although the book was not released during her lifetime, Barracoon: The Story of the Last Black Cargo was published in 2018. Many of the descendants of the Africans who were trafficked aboard the Clotilde still reside in northern Mobile, Alabama.

The National Park Service also listed the Africatown Historic District on the National Register of Historic Places in December 2012.

No comments