During the early and mid-1900s race riots were occurring across the country. One particular riot took place during the onset of the Great Depression, when lynching and other unjustifiable acts were increasing with economic troubles. The Sherman Riot of 1930 was one a major incident of racial violence in the United States. All over the country white tenant farmers were demonstrating hostility and hatred toward #Black people. The town of Sherman was the county’s banking, industrial, and educational center in Texas. The Southern Commission on the Study of Lynching reported in 1931 that Sherman felt the onset of the depression more keenly than other communities similar in size to Texas.

The incident occurred because a Black man, George Hughes, was accused of raping a young white woman; whom was never identified. Many people described Hughes as being “crazy” and just not in his right mind. However, Hughes admitted that he had been at the farm five miles southeast of Sherman on May 3, 1930, looking for the white woman’s husband, who owed him money for work. Hughes left when the woman told him that her husband was in the town of Sherman and would return later. But, later that day Hughes returned with a shotgun, demanded his wages again, and supposedly raped the woman. Crazy or not crazy, although Hughes admitted to being at the home, he never admitted to rape. Hughes shot at unarmed pursuers and police patrol cars who arrived to investigate what supposedly had taken place. With no where for Hughes to run, he eventually surrendered.

Hughes was later indicted for criminal assault by a special meeting of the grand jury in the Fifteenth District Court. Days before the trial rumors about the case began to spread. People were gossiping to neighbors telling their version of what had taken place. Some told that the white woman’s throat and breast had been mutilated, and she was not expected to live. It was later confirmed that the rumors being told were false. Hughes was removed from the jail to an undisclosed location as protection. Angry whites were gathering and wanted to get their hands on Hughes. Some angry mob members were allowed to walk through the jail to see for themselves that Hughes had been taken elsewhere. The crowd knew that sooner or later Hughes would show back up in the courtroom.

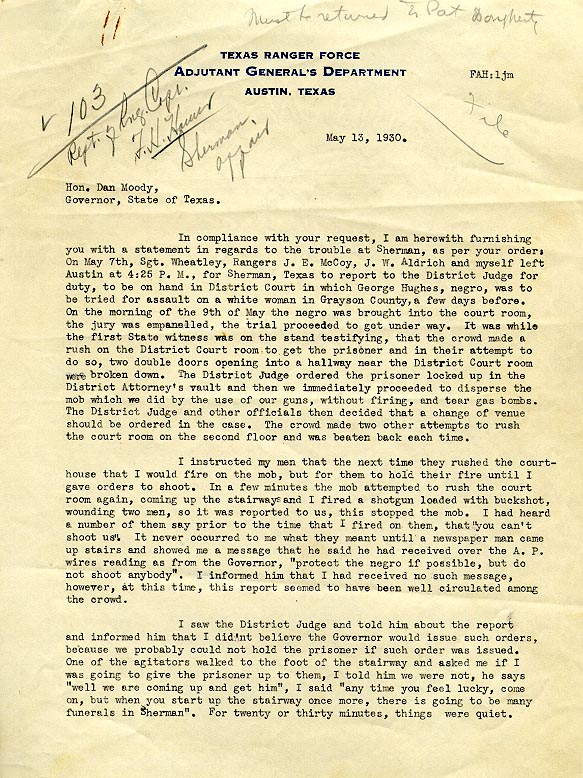

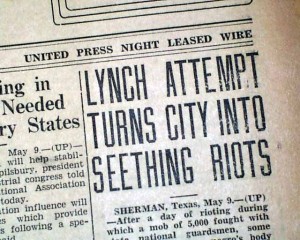

On May 9, Hughes was escorted to the county courthouse. Only a few people were allowed in the courtroom. But, a crowd from all over Texas had gathered outside the building, filled the hallways, corridors, and where they could find a spot. During the late morning, the crowd began to stone the courthouse, and the American flag was carried around to get the crowd going. The judge ruled that the case could not be tried in Sherman because there would be bloodshed. Two youths threw open cans of gasoline into the county tax collector’s office through a broken window, and a fire quickly spread throughout the building. The officials managed to escape, but when the deputies guarding Hughes offered to escort him out, Hughes chose to remain locked in the vault. Rangers attempted to rescue him but were cut off by flames. The mob held the firemen back and cut their hoses. By that evening only the walls of the building and the fireproof vault remained.

The angry mob tried to tear the walls of the vault. Guardsmen were injured by gunshots, but it didn’t stop leaders of the mob from working to get the vault open. By midnight the mob had opened the vault and had Hughes body. More than 5,000 people filled the courthouse yard and street. Hughes’s body was thrown from the vault, and dragged behind a car to the front of a drugstore in the black business section. The mob then took the body and hung it from a tree. The mob used whatever they could get their hands on to fuel the fire under Hughes hanging body. During the process the mob burned down many businesses in the area, all the businesses that were owned by Black people, and some of their homes as well. Because the mob burned down two Black undertaking business, Hughes body had to be turned over to a white undertaker. Hughes was buried on May 10 in Grayson County. No charges for the lynching was brought against fourteen suspects who were arrested for rioting. Out of the fourteen men in connection with the riot, only two were convicted, both received only two year sentences. Hughes’s lynching was the first of many more to come during the next months and years.

source:

4 Comments

magnificent publish, very informative. I wonder why the

opposite experts of this sector don’t understand

this. You should proceed your writing. I am confident, you’ve a huge readers’

base already!

Thank you for sharing your thoughts. I truly appreciate your

efforts and I am waiting for your next post thanks once again.

If you want to grow your familiarity simply keep visiting this

web page and be updated with the hottest gossip posted here.

Excellent way of telling, and fastidious article to take data

on the topic of my presentation subject, which i am

going to present in academy.