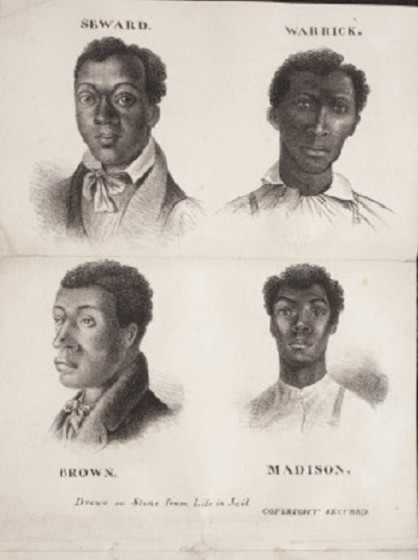

In the early summer of 1841, four black men – Charles Brown, Madison Henderson, James Seward, and Alfred Warrick – were put on trial. The men were convicted of arson, burglary, and murder, and were sentenced to death. By July 9, 1841, the men had been hanged. People were encouraged to purchase tickets at $1.50 a piece to join a steamboat excursion to watch the execution on Duncan’s Island. Roughly 20,000 people attended, which at the time was 75 percent of St. Louis’s population.

The crime that took the four men to the gallows in July 1841 had occurred three months earlier. On April 18, 1841, the townspeople of St. Louis woke up to the news that two young clerks, Jacob Weaver and Jesse Baker, had been murdered. The bank where the two worked also had been destroyed by fire. It was believed that the two clerks had walked in on a burglary in process after returning to their sleeping quarters after dinner. The burglars reportedly killed the clerks and set the bank on fire.

After the townspeople had time to think about what had taken place, they called a town’s meeting. At the meeting, the mayor at the time, John Daggett, offered a $5,000 reward for any information leading to the capture of the individuals responsible for the crime.

The big break came in the case when Edward Ennis, a free black barber in the city, began to spread gossip. He confided in a friend information about the murders. His friend then informed the authorities, who later picked up Ennis on April 25 to find out his information. Ennis was offered immunity in exchange for his cooperation. He later supplied the police with all the information they needed, including the names and locations of the four men who fled the city. The mayor encouraged the press to hold information that was released to them in order to give the police enough time to track down the suspects.

On April 17, Henderson, Warrick, Seward, and Brown had supposedly met on the St. Louis levee at dusk to carry out the robbery, which they had been planning for a few days. They planned to hit the Pettus Bank on Water Street, and they had already decided to kill the young clerk whom they expected to meet when they entered the bank. Henderson carried an iron crowbar which was hidden under his sleeve.

They walked into the bank and asked Jesse Baker, the clerk, to examine a bank note. As the young man turned, Henderson struck him and knocked the young man unconscious. As the men had agreed on previously, the three others also came in; they each struck a blow in turn until no signs of life remained. The men could not find the vault keys and attempted to pry open the vault. While doing so, they were interrupted by Jesse Baker’s roommate, Jacob Weaver; the four men also allegedly beat him to death.

According to his testimony, Ennis had arrived home about ten o’clock on the night of the crime. An hour or so later, Henderson knocked on the door, and Ennis let him in. While sitting alone in the dark together, Henderson confessed to Ennis that he and three other men had unsuccessfully tried to rob a bank, and in the process, they murdered two clerks. Henderson still had the murder weapon in his possession. However, he gave it to Ennis to dispose of in the privy vault at the rear of the property, where authorities later found it.

When Seward was captured, he admitted to his involvement in the attempted robbery, identified Brown and Henderson as the murderers, and also implicated Ennis as a conspirator. Seward was the first to arrive in St. Louis to face trial.

On May 10, Madison Henderson, James Seward, and Alfred Warrick appeared before Judge James Bowlin to be charged with the murders of Baker and Weaver. All three pled not guilty. All four men gave a narrative of their lives; however, the narrative that stood out was that of Charles Brown. Brown claimed to be a paid agent of the Ohio Anti-Slavery Society, and related in detail how abolitionist organizations operated. He explained that paid agents, such as himself, went from town to town to identify potential runaways and persuade them to leave. As a cover for any of his illegal activities, he worked in various capacities in New Orleans hotels or as crew on one of the riverboats. The stories that readers read of the four men sparked fear and fascination. The four men were lynched during the summer of 1841.

source:

http://collections.mohistory.org/media/CDM/gateway/83.pdf

2 Comments

has anything changed and its 2020 trump is da shot caller don’t forget the park in N Y City

Ennis, it is always that one. The one that will turn his mama, in to receive favoritism with the white man.