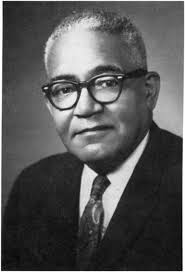

Horace Mann Bond served as the first president of Fort Valley State College and as president of Lincoln University from 1945 to 1957. He was also the father to the acclaimed civil rights activist, Julian Bond.

Bond was born on November 8, 1904, in Nashville, Tennessee, to Jane Alice Browne and James Bond. Both his parents had graduated from Oberlin College in Ohio; they were influential people in their local community and encouraged their children to also get a good education. He graduated with honors from Lincoln University in Pennsylvania at age 19 in 1923. He also obtained membership in Kappa Alpha Psi fraternity.

After graduating college, Bond taught at several universities while completing his doctorate, including Langston University in Langston, Oklahoma; Fisk University and Dillard University in New Orleans, Louisiana. He worked his way up in academic administration, proving his leadership abilities by becoming dean at Dillard University in 1934, and chairman of the education department at Fisk University later in the 1930s. He was later became the first president of Fort Valley State College, in Fort Valley, Georgia, where he was appointed in 1939 and served until 1945.

In 1945, Bond was selected as president of Lincoln University, the first African American to be appointed to that position. He served at his alma mater until 1957. During those years, he started years of historical research for Lincoln University. Later in 1953, together with historians John Hope Franklin and C. Vann Woodward, Bond did research that helped support the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People in the landmark U.S. Supreme Court case of Brown v. Board of Education in 1954.

Bond’s first publications were in the NAACP magazine, The Crisis, in 1924. In 1956, a group of White Southern Senators signed the Southern Manifesto in opposition to racial integration and the Brown vs. Board of Education decision. They argued that African Americans were not sufficiently intelligent to participate in the same schools as white students.

In response, Bond published a parody of the arguments of the signing senators by using the data he had first collected and published in 1924. He published the results in an essay titled “Intelligence of Congressmen Who Signed the ‘Southern Manifesto’ as Measured by IQ Tests.” In this article, Bond concluded that, based on the Army intelligence tests, the average score of the signing senators was in the lowest 20 percent of American white citizens. On average, signatories attended colleges of the lowest ten percent of median national scores, and had a constituency whose majority was in the intelligence category of “morons.” Consequently, Bond concluded that the logical policy recommendation, following the reasoning of the senators, would be to segregate the slow-learning signatories into a group together, in which they could receive “remedial attention to make up for their basic deficiencies.”

The essay was published by the NAACP and attracted widespread hilarity or uproar, depending on viewpoint. Bond later referred to the essay as “his little foolishness,” but he maintained that he had made a significant point.”

Through his work with the Julius Rosenwald Fund, Bond was a powerful figure in directing and attracting philanthropic support to African-American schools. Horace M. Bond died on Dec. 21, 1972.

source:

http://aaregistry.org/historic_events/view/horace-m-bond-educator-and-trailblazer

No comments