In 1897, President McKinley appointed Frazier Baker as postmaster of Lake City, South Carolina. However, to no surprise, local whites objected the act and set out on a mission to force his removal from the position. The McKinley administration appointed hundreds of blacks to postmaster across the Black Belt.

A boycott of the Lake City post office was initiated, and petitions calling for Baker’s dismissal were circulated. One complaint was that Baker, a member of the Colored Farmers Alliance, had cut mail delivery from three times a day to just one after threats against his life were made.

A postal inspector arrived in the town to investigate the complaints from the white citizens. The inspector recommended the post office be closed. After hearing the inspector wanted the post office closed, a white mob gathered and burned it down to keep the building from being rented out to another black person.

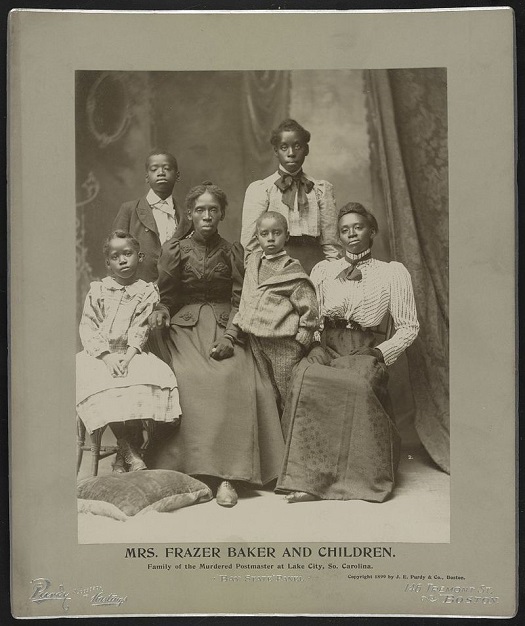

Fortunately, another location was found for Baker to work on the outskirts of town with less racial tension. Once settled in his new location, Baker sent for his wife and six children. Nevertheless, threats remained constant against Baker’s life since whites remained hostile to his presence.

On February 21, 1898, the Baker family awoke to find their house–which was also the post office–on fire. Baker tried to put the fire out with very little success. He sent his son to find help, but when his son opened the door, he was met with gunfire. Baker pulled him back into the house, but as the fire grew, Baker and his wife knew they had to get out.

As they were making their way to the door, a bullet struck and killed their two-year-old daughter. His wife was wounded with the same bullet. However, Baker’s wife was able to rally the remaining members of her family and they escaped to a neighbor’s home. Only two out of the six children were not harmed. The lynching was defended by those who agreed with South Carolina Senator Benjamin Tillman’s appraisal of the “proud people” of Lake City’s refusal to receive “their mail from a nigger.”

Ida B. Wells-Barnett denounced the lynching and noted that the lynchers hadn’t even bothered with the pretense of Baker having committed a crime. President McKinley argued that Baker’s murder “was a federal matter, pure and simple.” McKinley assured Wells that an investigation was underway. While in Washington, she also urged Congress to provide support to the survivors, but attempts were unable to overcome southern opposition.

Thirteen men were indicted for the murder, conspiracy to commit murder, assault, and destruction of mail on April 7, 1899. Lavina Baker and her children remained in Boston, out of public life. Unfortunately, the surviving Baker children all fell victim to the fatal tuberculosis epidemic.

sources:

http://historymatters.gmu.edu/d/5486/

https://books.google.com/books?id=UWG-o7b5HGwC&pg=PA190#v=onepage&q&f=false

3 Comments

If you wish for to obtain much from this article then you have to

apply these techniques to your won blog.

I think the admin of this site is truly working hard for his

site, for the reason that here every data is quality based stuff.

Wonderful goods from you, man. I have understand your stuff previous to and you are

just too magnificent. I really like what you have acquired here, certainly like what you are stating and the way

in which you say it. You make it enjoyable and you still take care of to keep it wise.

I cant wait to read much more from you. This is really

a terrific website.