May 31 – June 1, 1921: The attacks on Black Wall street begins.

The Tulsa Race Riot was a large-scale, racially motivated conflict on May 31 and June 1, 1921, in which whites attacked the black community of Tulsa, Oklahoma, which included aerial attacks.

In an effort to completely destroy the Greenwood District of Tulsa, firemen were held at gunpoint by whites making it impossible to put out the flames.

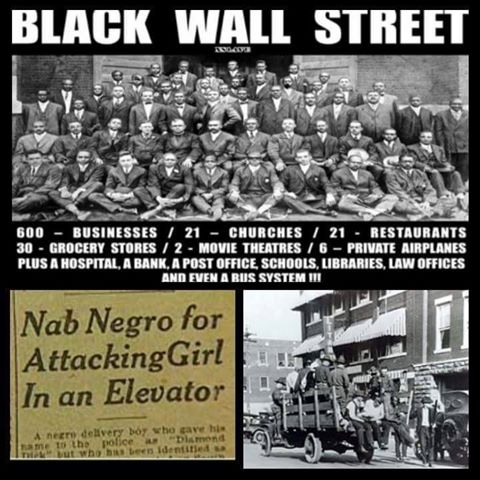

It resulted in the Greenwood District, also known as ‘the Black Wall Street’ and the wealthiest black community in the United States, being burned to the ground.

During the 16 hours of the assault, more than 800 blacks were admitted to local white hospitals with injuries (the black hospital was burned down), and police arrested and detained more than 6,000 black Greenwood residents at three local facilities, in part for their protection.

An estimated 10,000 blacks were left homeless, and 35 city blocks composed of 1,256 residences were destroyed by fire. The official count of the dead by the Oklahoma Department of Vital Statistics was 39, but other estimates of black fatalities have been up to about 300.

The events of the riot were long omitted from local and state histories. “The Tulsa race riot of 1921 was rarely mentioned in history books, classrooms or even in private. Blacks and whites alike grew into middle age unaware of what had taken place.” With the number of survivors declining, in 1996, the state legislature commissioned a report to establish the historical record of the events, and acknowledge the victims and damages to the black community.

Released in 2001, the report included the commission’s recommendations for some compensatory actions. The state has passed legislation to establish some scholarships for descendants of survivors, economic development of Greenwood, and a memorial park to the victims in Tulsa. The latter was dedicated in 2010.

BACKGROUND:

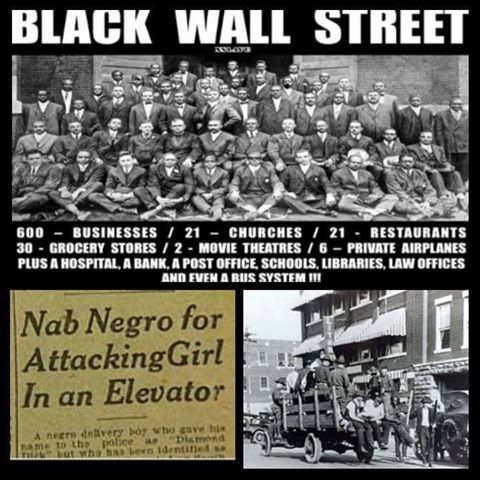

The traditionally black district of Greenwood in Tulsa had a commercial district so prosperous it was known as “the Negro Wall Street” (now commonly referred to as “the Black Wall Street”). Blacks had created their own businesses and services in their enclave, including several groceries, two independent newspapers, two movie theaters, nightclubs, and numerous churches. Professional black doctors, dentists, lawyers and clergy served the community. Because of residential segregation in the city, most classes of blacks lived together in Greenwood. They selected their own leaders, and there was capital formation within the community. In the surrounding areas of northeastern Oklahoma, blacks also enjoyed relative prosperity and participated in the oil boom.

MAY 31ST ATTACKS:

The riot began because of an alleged assault of a white woman, Sarah Page, by an African American man, Dick Rowland on May 30th.

The morning after the alleged incident, Detective Henry Carmichael and Henry C. Pack, a black patrolman, located Rowland on Greenwood Avenue and detained him. Pack was one of two black officers among the city’s approximately 45-man police force. Rowland was initially taken to the Tulsa city jail at First and Main. Late that day, Police Commissioner J. M. Adkison said he had received an anonymous telephone call threatening Rowland’s life. He ordered Rowland transferred to the more secure jail on the top floor of the Tulsa County Courthouse.

Word quickly spread in Tulsa’s legal circles. As patrons of the shine shop where Rowland worked, many attorneys knew him. Witnesses recounted hearing several attorneys defending him in personal conversations with one another. One of the men said, “Why I know that boy, and have known him a good while. That’s not in him.”

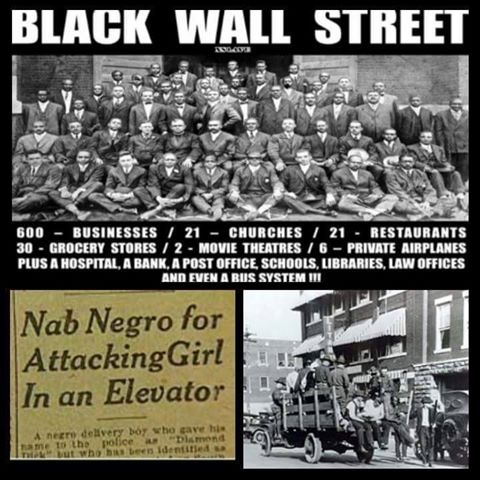

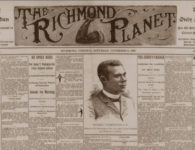

•Newspapers•

The Tulsa Tribune, one of two white-owned papers published in Tulsa, broke the story in that afternoon’s edition with the headline: “Nab Negro for Attacking Girl In an Elevator”, describing the alleged incident.

According to some witnesses, the same edition of the Tribune included an editorial warning of a potential lynching of Rowland, and entitled “To Lynch Negro Tonight”. The paper was known at the time to have a “sensationalist” style of news writing. All original copies of that issue of the paper have apparently been destroyed, and the relevant page is missing from the microfilm copy, so the exact content of the column (and whether it existed at all) remains in dispute.

•Courthouse Stand-Off•

The afternoon edition of the Tribune hit the streets shortly after 3 p.m., and soon news of the potential lynching spread. By 4 p.m., the local authorities were on alert. White people began congregating at and near the Tulsa County Courthouse.

By sunset at 7:34 p.m., the several hundred whites assembled outside the courthouse appeared to have the makings of a lynch mob. Willard M. McCullough, the newly elected sheriff of Tulsa County, was determined to avoid events such as the 1920 lynching of Roy Belton in Tulsa, which occurred during the term of his predecessor. The sheriff took steps to ensure the safety of Rowland. McCullough organized his deputies into a defensive formation around Rowland, who was terrified. The sheriff positioned six of his men, armed with rifles and shotguns, on the roof of the courthouse. He disabled the building’s elevator, and had his remaining men barricade themselves at the top of the stairs with orders to shoot any intruders on sight. The sheriff went outside and tried to talk the crowd into going home, but to no avail. According to an account by Ellsworth, the sheriff was “hooted down”.

About 8:20 p.m., three white men entered the courthouse, demanding that Rowland be turned over to them. Although vastly outnumbered by the growing crowd out on the street, Sheriff McCullough was determined to prevent another lynching and turned the men away.

•Help Is Offered•

A few blocks away on Greenwood Avenue, members of the black community were gathering to discuss the situation at the courthouse. Given the recent lynching of Roy Belton, a white man, they believed that Rowland was greatly at risk. The community was determined to prevent the lynching of another young black man, but divided about the tactics to be used. Young, militant World War I veterans were preparing for a battle by collecting guns and ammunition. Older, more prosperous men feared a destructive confrontation that likely would cost them dearly. O. W. Gurley walked to the courthouse, where the sheriff talked with him and assured that there would be no lynching. Returning to Greenwood, Gurley tried to calm the militants, but failed. About 7:30 p.m., a group of approximately 30 black men, armed with rifles and shotguns, decided to go to the courthouse and support the sheriff and his deputies to defend Rowland from the mob. Assuring them that Rowland was safe, the sheriff and his black deputy, Barney Cleaver, encouraged the men to return home.

•Whites Gather Arms•

Having seen the armed blacks, some of the more than 1,000 whites at the courthouse went home for their own guns. Others headed for the National Guard armory at Sixth Street and Norfolk Avenue, where they planned to arm up. The armory contained a supply of small arms and ammunition. Major James Bell of the 180th Infantry, had already learned of the mounting situation downtown and the possibility of a break-in; he took appropriate measures to prevent this. He called the commanders of the three National Guard units in Tulsa, who ordered all the Guard members to put on their uniforms and report quickly to the armory.

When a group of whites arrived and began pulling at the grating over a window, Bell went outside to confront the crowd of 300–400 men. Bell told them that the Guard members inside were armed and prepared to shoot anyone who tried to enter. After this show of force, the crowd withdrew from the armory.

At the courthouse, the crowd had swollen to nearly 2,000, many of them now armed. Several local leaders, including Reverend Charles W. Kerr, pastor of the First Presbyterian Church, tried to dissuade mob action. The chief of police, John A. Gustafson, later claimed that he tried to talk the crowd into going home.

Anxiety on Greenwood Avenue was rising. The black community was worried about the safety of Rowland. Small groups of armed black men began to venture toward the courthouse in automobiles, partly for reconnaissance, and to demonstrate they were prepared to take necessary action to protect Rowland.

Many white men interpreted these actions as a “Negro uprising” and became concerned. Eyewitnesses reported gunshots, presumably fired into the air, increasing in frequency during the evening.

•Help Is Offered AGAIN•

In Greenwood, rumors began to fly – in particular, a report that whites were storming the courthouse. Shortly after 10 p.m., a second, larger group of approximately 75 armed black men decided to go to the courthouse. They offered their support to the sheriff, who declined their help. According to witnesses, a white man is alleged to have told one of the armed black men to surrender his pistol. The man refused, and a shot was fired. That first shot may have been accidental, or meant as a warning shot; it was a catalyst for an exchange of gunfire.

THE RIOT:

Gunshots triggered an almost immediate response by the white men, many of whom fired on the blacks, who continued firing back at the whites. The first “battle” was said to last a few seconds or so, but took a toll, as several white and black lay dead or dying in the street. The black contingent retreated toward Greenwood. A rolling gunfight ensued.

The armed white mob pursued the black group toward Greenwood, with many stopping to loot local stores for additional weapons and ammunition. Along the way innocent bystanders, many of whom were leaving a movie theater after a show, were caught off guard by the mob and began fleeing. Panic set in as the white mob began firing on any blacks in the crowd. The mob also shot and killed at least one white man in the confusion.

At around 11 p.m., members of the Oklahoma National Guard unit began to assemble at the armory to organize a plan to subdue the rioters. Several groups were deployed downtown to set up guard at the courthouse, police station, and other public facilities. Members of the local chapter of the American Legion joined in on patrols of the streets. The forces appeared to have been deployed to protect the white districts adjacent to Greenwood. This manner of deployment led to the National Guard being set in apparent opposition to the black community. The National Guard began rounding up blacks who had not returned to Greenwood and taking them to the Convention Hall on Brady Street for detention.

Many prominent Tulsa whites also participated in the riot, including Tulsa founder and KKK member W. Tate Brady who participated in the riot as a night watchman. He reported seeing “five dead negroes,” including one man who was dragged behind a car by a noose around his neck.

Close to midnight, white rioters again assembled outside the courthouse. It was a smaller group but more organized and determined. They shouted in support of a lynching. When they attempted to storm the building, the sheriff and his deputies turned them away and dispersed them.

Want to learn more about Black Wall Street and what we can do 95 years later to remember this massacre. Check out this DVD

No comments