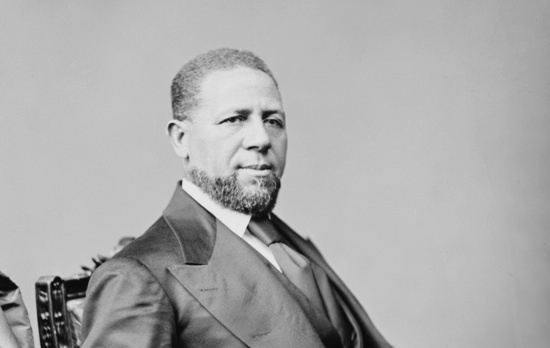

When Senator Hiram Revels of Mississippi—the first African American to serve in Congress—toured the United States in 1871, he was introduced as the “Fifteenth Amendment in flesh and blood.”1 Indeed, the North Carolina-born preacher personified African-American emancipation and enfranchisement. On January 20, 1870, the state legislature chose Revels to briefly occupy a U.S. Senate seat, previously vacated by Albert Brown when Mississippi seceded from the Union in 1861.2 As Senator Henry Wilson of Massachusetts escorted Revels to the front of the chamber to take his oath on February 25, the Atlanta Constitution reported that “the crowded galleries rose almost en masse, and each particular neck was stretched to its uttermost to get a view. A curious crowd (colored and white) rushed into the Senate chamber and gazed at the colored senator, some of them congratulating him. A very respectable looking, well dressed company of colored men and women then came up and took Revels captive, and bore him off in glee and triumph.”3 The next day, the Chicago Tribunejubilantly declared that “the first letter with the frank of a negro was dropped in the Capitol Post Office.”4 But Revels’s triumph was short-lived. When his appointment expired the following year, a leading white Republican, former Confederate general James Alcorn, took his place for a full six-year term.

In many respects, Revels’s service foreshadowed that of the black Representatives who succeeded him during Reconstruction—a period of Republican-controlled efforts to reintegrate the South into the Union. They, too, were largely symbols of Union victory in the Civil War and of the triumph of Radical Republican idealism in Congress. “[The African-American Members] have displaced the more noisy ‘old masters’ of the past,” a reporter with the Chicago Tribune wrote, “and, in their presence in [Congress], vindicate the safety of the Union which is incident to the broadest freedom in political privileges.”5 The African-American Representatives also symbolized a new democratic order in the United States. These men demonstrated not only courage, but also relentless determination.They often braved elections marred by violence and fraud. With nuance and tact they balanced the needs of black and white constituents in their Southern districts, and they argued passionately for legislation promoting racial equality. However, even in South Carolina, a state that was seemingly dominated by black politicians, African-American Members never achieved the level of power wielded by their white colleagues during Reconstruction. Though pushed to the margins of the institutional power structure, the black Representatives nevertheless believed they had an important role as advocates for the United States’s newest citizens.

article found @http://history.house.gov/Exhibitions-and-Publications/BAIC/Historical-Essays/Fifteenth-Amendment/Introduction/

No comments