On Monday, every player in Major League Baseball will wear Jackie Robinson’s No. 42 to honor the player who broke baseball’s color barrier on April 15, 1947. The country is also marking the centennial of Robinson’s birth on Jan. 31, 1919 throughout the year.

#Jackie42 forever. pic.twitter.com/S3cKN4lMtt

— MLB (@MLB) April 15, 2019

But the first African American to play regularly in the big leagues wasn’t the Brooklyn Dodgers second baseman, it was Moses Fleetwood “Fleet” Walker.

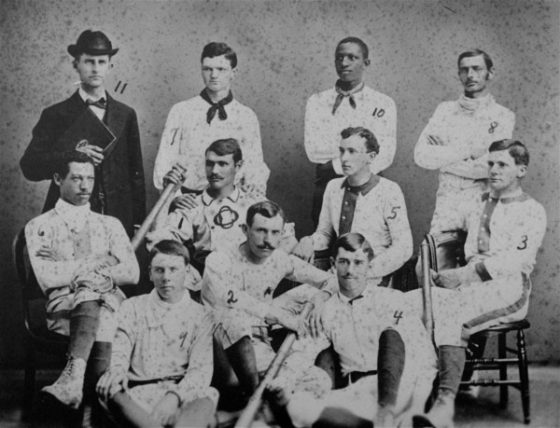

On May 1, 1884, the 26-year-old Walker was the catcher for the Toledo Blue Stockings in their opening game in the then-major league American Association. Six decades later, while Robinson was hailed as a pioneer, Walker was seen more as a curiosity.

Before a June game against the original Washington Nationals, The Washington Post noted that Toledo’s catcher “is a colored man, and no doubt many will attend the game to see our ‘colored brother’ in a new role.” After Toledo won, The Post reported that Walker played in “fine style” catching star pitcher Tony Mullane.

Like many of Walker’s white teammates, Mullane respected the barehanded catcher as a player but not as an equal. Walker “was the best catcher I ever worked with,” Mullane said years later, “but I disliked a Negro, and whenever I had to pitch to him I pitched anything I wanted without looking at his signals.”

Walker first gained attention playing for Oberlin College in Ohio and then the University of Michigan, where he studied law. In 1883, the Toledo team recruited him to play in the new Northwestern League, a minor league. The club in Peoria, Ill., tried to ban Walker, but the demand “met with such disapprobation” that it was withdrawn, one newspaper reported.

The personable Walker was popular with many white sportswriters. The Sporting News later described him as “an avid reader of high-grade literature and a brilliant conversationalist.” But Walker faced discrimination on and off the field.

In Fort Wayne, Ind., a local newspaper reported, a “priggish head waiter” at one restaurant refused to seat Walker, who was said to be well-paid. Walker, the paper said, “receives more money in a week than the big-headed waiter had in six months, and is far more advanced mentally of the white man.” The waiter was fired.

Walker was never a great player, but was described as “a plucky catcher, a hard hitter and a daring and successful base runner.” He led Toledo to the Northwestern League pennant in 1883. The next season Toledo joined the American Association, which added four teams, including the Washington Nationals and the forerunner of the Brooklyn Dodgers.

Walker hit a solid .263 in 1884 but played only 42 games because of a rib injury. (His brother, Weldy, also played a few games in the outfield.) Walker often faced racial taunts from fans, as Robinson would later. Before a trip to play in Richmond, Toledo’s manager received this letter:

“We the undersigned do hereby warn you not to put up Walker, the negro catcher, the evenings you play in Richmond, as we could mention the names of 75 determined men who have sworn to mob Walker if he comes on the ground in a suit. We hope you will listen to our words of warning, so that there will be no trouble, but if you do not there certainly will be. We only write this to prevent much bloodshed, as you alone can prevent.” Walker did not play.

Toledo cut Walker from the team after the 1884 season, and he never played another major league baseball game. But he continued to play in the minor leagues. At Newark in the top-level International League, a sportswriter wrote a poem about him:

There is a catcher named Walker, Who behind the plate is a corker. He throws to a base, with ease and grace. And steals ‘round the bags like a stalker.

A teammate on the Newark Little Giants was African American pitcher George Stovey, who in 1886 led the International League with 35 wins. By 1887, the 12-team league had seven black players, including Buffalo star Frank Grant, who wore wooden shin guards playing second base to deflect vicious, spikes-high slides aimed at him by white base runners. The number of black players began to concern the league’s white owners and some white players.

In July 1887, the National League’s Chicago White Stockings (now the Chicago Cubs) were scheduled to play an exhibition game against the Little Giants in Newark. But Chicago’s star player-manager Adrian “Cap” Anson, a known racist, refused to let his team play if Newark’s black players did. So Walker and Stovey were benched for the game.

That day International League owners voted to ban the signing of any new black players; those already under contract were allowed to continue. The ban eventually spread to become baseball’s unwritten rule barring African American players until Jackie Robinson joined Brooklyn’s farm team in Montreal in 1946.

By his final year in 1889 playing for Syracuse, Walker was the lone black player left in the International League. He had always led a lonely life. He often slept on park benches and in railroad stations because hotels refused to allow him to stay with his white teammates. Once, he sued a restaurant in Detroit for refusing to serve him.

Beneath Walker’s calm exterior lurked “a darker side that would be constantly goaded by racial tensions,” wrote David W. Zang in his book, “Fleet Walker’s Divided Heart.” In Toronto, Walker was caught with a loaded gun after threatening to shoot a taunting fan. In 1891, after he left baseball, Walker was charged with second-degree murder in Syracuse for fatally stabbing one of several white men who accosted him on a city street. An all-white jury acquitted him.

Walker returned to his home state of Ohio, where he owned a movie theater with his second wife. Walker’s life left him embittered about race relations in America. In 1908 he wrote a book, “Our Home Colony,” that advocated the separation of the races.

A life is not important except in the impact it has on other lives.” – Jackie Robinson

— Cincinnati Reds (@Reds) April 15, 2019

Thank you, #Jackie42. pic.twitter.com/7inUKK5AWA

By contrast, Robinson was a leader for racial integration. He led Brooklyn to six National League pennants and one World Series championship. In 1962, he was elected to the Baseball Hall of Fame. After Robinson retired, he became a leader in the civil rights movement. He died of a heart attack in 1972 at 53, and his obituary appeared on the front pages of newspapers across the country.

Walker’s death in 1924 at the age of 67 was unacknowledged by white America. He remains a historical footnote to this day, mostly recognized by baseball aficionados.

This article was first found at https://www.washingtonpost.com/history/2019/04/15/first-african-american-major-leaguer-wasnt-who-you-think/?noredirect=on&utm_term=.80497832cbf7

4 Comments

?♐??”I”L☯️¥€,..THE SPORT AS A° YOUNSTER I,..PLAYED AS FRIST-STING PICTHER~BUT ALSO AS =A=LEFT•AMBIDEXTROUS•ORIENTED TEAM♤MAT€,..”I”ENDURED SOME OF TH€ MOST HARSHEST PREJUDICE THAT A =BLACK✡MAN= COULD MUSTER¿¿¿!!!!?♎?

This is an incredibly amazing story of incredible tolerance of a intolerable time of a simple minded people thank God that stupidity didn’t prevail and people evolved to a higher place of intellect we as a nation have still a long ways to go however we as a nation have come a long long ways I must say that I’m proud of America and proud to be an American we as a people continue to move on up and inspire to move even further thank you for sharing this story I’m glad that I had the opportunity to read it.

This is an informative article, but it is not thorough enough.

William Edward. White preceded Fleetwod.Walker and his brother Weldon Walker..

Fleetwood Walker also had a brother Weldon “Weldy” Walker who played baseball and hockey for professional teams.

Way before Jackie Robinson these men had …. See for yourself .

William Edward White – Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

image

William Edward White – Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

William Edward White (1860–1937) was a 19th-century baseball player. He played as a substitute in one professional baseball game for the Providence Grays of the Nat…

View on en.wikipedia.org

Preview by Yahoo

Especially interesting is the scholarly work of Moses Fleetwood Walker brother of Weldy Walker.

“…. he recommended that African Americans emigrate to Africa: “the only practical and permanent solution of the present and future race troubles in the United States is entire separation by emigration of the Negro from America”

He warned “The Negro race will be a menace and the source of discontent as long as it remains in large numbers in the United States. The time is growing very near when the whites of the United States must either settle this problem by deportation, or else be willing to accept a reign of terror such as the world has never seen in a civilized country.”

Moses Fleetwood Walker – Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

image

Moses Fleetwood Walker – Wikipedia, the free encyclopedi…

Moses Fleetwood “Fleet” Walker (October 7, 1856 – May 11, 1924) was an American baseball player, inventor, and author. He is credited by some with being the first A…

View on en.wikipedia.org

Preview by Yahoo

“Our Home Colony: A Treatise on the Past, Present, and Future of the Negro Race in America.” – Moses Fleetwood Walker

Weldy Walker – Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

image

Weldy Walker – Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

Weldy Wilberforce Walker (July 27, 1860 – November 23, 1937), sometimes known as Welday Walker and W. W. Walker, was an American baseball player. In 1884, h…

View on en.wikipedia.org

Weldy Walker’ open letter published in “Sporting Life”:

Weldy Walker wrote: ” The law is a disgrace to the present age, and reflects very much upon the intelligence of your last meeting, and casts derision at the laws of Ohio – the voice of the people – that say all men are equal. I would suggest that your honorable body, in case that black law is not repealed, pass one making it criminal for a colored man or woman to be found on a ball ground … There should be some broader cause – such as lack of ability, behavior and intelligence – for barring a player, rather than his color. It is for these reasons and because I think ability and intelligence should be recognized first and last – at all times and by everyone – I ask the question again, ‘Why was the law permitting colored men to sign repealed, etc.?”

Very informative.