By Lestey Gist, The Gist of Freedom

“I was bred as an outcast, part Negro and part Seminole, in my early years raised as an Indian.”

–Willie Stargell, Black Seminole (1940 – 2001)

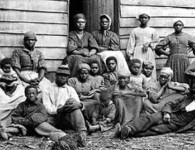

Long before Florida was a U. S. state, it was home to diverse freedom seekers who found refuge from slavery, established thriving communities and prospered on Florida’s frontier.

Florida’ original inhabitants were southeastern American Indians who had occupied the land for many generations. These were the native populations that European explorers such as Panfilo de Narvaez and Hernando De Soto encountered when they made landfall on the Florida peninsula and set out to explore the interior of North America.

As Europeans sought to colonize the New World, southeastern North America became a contested area for Spain, England and France. After 1776, the United States also joined the colonial struggle for control of the southeast. The Florida peninsula in particular was much sought after by imperials who hoped to control the rich and strategic shipping routes in the Atlantic Ocean and the Gulf of Mexico.

As early as 1687, the Spanish government had unofficially offered asylum to British enslaved African, in an attempt to break Britain’s economic stronghold in the borderlands around Spanish Florida. In 1693 that asylum was made official when the Spanish crown offered limited freedom to any enslaved Africans escaping to Spanish Florida who would accept Catholicism.

When the English established the border colony of Georgia in 1733, the Spanish Crown made it known once again that runaways would find freedom in Spanish Florida, in return for Catholic conversion and a term of four years in service to the crown.

Incoming freedom seekers were recognized as free, mustered into the Spanish militia and placed into service at the Gracia Real de Santa Teresa de Mose military fort north of St. Augustine, which was established in 1783. Their leader, who had fled from slavery in the English Carolina colony, was known to the Spaniards as Francisco Menendez.

Florida was ceded to the English in 1763 and most of the inhabitants, including many black militia troops, migrated to Cuba with the evacuating Spanish. Other black militia members chose to stay and make their lives in English Florida.

The incoming English government soon learned that Florida was a magnet to Africans and African Americans in North America who sought freedom from slavery. Once in Florida, freedom seekers encountered the Creek and Seminole Native Americans who had established settlements there at the invitation of the Spanish government. Those who chose to make their lives among the Creeks and Seminoles were welcomed into Native American society.

Governor John Moultrie wrote to the English Board of Trade in 1771 that “It has been a practice for a good while past, for negroes to run away from their Masters, and get into the Indian towns, from whence it proved very difficult to get them back.”

When British government officials pressured the Seminoles to return runaway slaves, they replied that they had merely given hungry people food, and invited the slaveholders to catch the runaways themselves.

British rule, government officials had presented Creek and Seminole leaders with “King’s gifts” of enslaved Africans in return for service to the crown. Some Seminole chiefs also began to buy enslaved Africans at this time; noting the prestige that both the Spanish and English attached to slave ownership. They frequently paid in cattle for such purchases. By the 1790s, wealth was increasingly determined by slave ownership.

The Seminoles’ concept of slavery was very different than that of the whites. While it is true that the Creeks and Seminoles had taken slaves before blacks came among them in appreciable numbers, these were frequently war captives, who were expected to fill the labor demands of warriors lost in battles. Some were eventually adopted into the tribe, especially if they intermarried with their new captors, which was often encouraged.

Even though early Seminole settlers in Florida are said to have owned “a considerable number of Yamassee slaves”, children born to Seminole Indians and Yamassee captives were not considered slaves. Thus, Seminole society had no cultural antecedent of chattel slavery to govern their relations with their new “possessions.”

When the new wave of runaway slaves began to pour into Florida, The Seminoles provided them with tools for building houses and planting crops. Black Seminoles lived apart from their masters in a sort of vassalage, enjoyed great personal freedom, owned property and livestock, and were indebted to their “masters” only for a share of their yearly productions, and for military allegiance.

Inhabitants of each town were formally linked by tribute and allegiance obligations to the Seminole village of their master. These Africans, an Indian agent reported, also had “horses, cows and hogs, with which the Indian owner never presumed to meddle”.

They were of course required to provide the Seminoles with a portion of the slaughter, but retained for themselves all of their surplus productions from animal husbandry. The ‘owner’ provided protection, and the ‘slave’ paid a modest amount in return. This arrangement was, obviously, quite different from traditional plantation bondage.

By the time of the Revolutionary War, Florida had been a haven for runaway slaves for more than seventy years. The outbreak of hostilities of the Revolution afforded enslaved persons yet another opportunity to give their masters the slip, and they did so in great numbers. Many of these freedom seekers found shelter among the Seminoles.

At the beginning of the Revolutionary War, there were already established Black Seminole villages near major Seminole towns with an estimated 430 inhabitants. By the end of the Revolution, hundreds of East Florida plantation slaves were unaccounted for. Some fled to the Seminoles, while others established maroon communities, encountered little colonial government oversight and enjoyed peaceful relations with Seminoles and Black Seminoles.

By 1800, Black Seminoles and maroons had established several more villages in the area between the Apalachicola River and Tampa Bay.

Many other aspects of Seminole and Black Seminole existence were the same: “The economic arrangements of the black and Indian towns were similar, being based upon communal agriculture and hunting, the only significant difference being that the Africans apparently were the more successful farmers and owned more property than the Seminoles”.

While many aspects of the two groups’ daily lives were similar, others were quite distinct. Although the Black Seminoles quickly mastered the language of their allies, their primary language was a Creole tongue related to Gullah.

Religious beliefs and traditions also differed from those of the Seminole and frequently incorporated African, Creole, Spanish, and Indian elements, reflecting the diverse origins and experiences of Black Seminole society members.

The first Black Seminoles were a culturally diverse group of individuals who drew together for a common purpose: to pursue the relative freedom of life among American Indians over enslavement to the Europeans or Americans.

Some had been born in Africa and were first generation former slaves, while others were born into plantation slavery. Some were skilled craftpersons; having been sailors, carpenters, cooks, bakers, shoemakers and other technicians in servitude.

As time passed, others were born among the Seminole or other Indian nations, and followed their customs from birth. Thus diverse life experiences and cultural traditions contributed to the amalgam that was Black Seminole society.

The earliest Black Seminole settlements were near Seminole towns in the north and central peninsula in present-day Alachua, Hernando, Leon and Levy counties. Documentary accounts of the earliest Seminole settlements are sparse and rarely mention the names of associated Black Seminole villages or their occupants. It is only after 1812 that Florida’s many Black Seminoles come into historical focus through documentary accounts.

“That’s where the future lies, in the youth of today.” –Willie Stargell, Black Seminole

Source: Facebook

No comments