Each year, along with hat shopping, forecast watching, and amateur handicapping, the Kentucky Derby brings with it a sense of the state’s rich history. But whose history is it?

Today’s thoroughbreds are piloted around the racetrack by jockeys who are mostly white and Latino. But in the early days of racing, black jockeys dominated.

In fact, in the inaugural Kentucky Derby in 1875, only one rider was white. That race was won by Aristides, ridden by Oliver Lewis.

But the decline of black jockeys in the Derby and the rest of thoroughbred racing is intricately tied to the history of race and economics in the U.S., experts said.

The early dominance of black jockeys was a result of Antebellum customs. In the time of slavery, enslaved people were often the caretakers of horses on plantations, said Teresa Genaro, freelance turf writer and founder of Brooklyn Backstretch.

“What happened was that you had generation after generation of young black men who grew up around horses and grew up riding horses,” she said.

“The white plantation owners and white slave owners put people that they really trusted in charge of their horses, because their horses are obviously expensive, and necessary to the success of their plantations.”

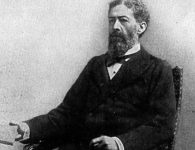

Decades after the end of slavery, black jockeys remained prominent in racing, riding 15 of the first 28 Kentucky Derby winners. Some became widely celebrated, including Isaac Burns Murphy and James “Jimmy” Winkfield.

But the economic aftermath of the Civil War in the South, and the abolition of slavery, changed the lives of black jockeys.

“All the sudden you have generations of black horsemen who had never known slavery. They were independent autonomous people, and white people began to feel really threatened by that,” Genaro said.

Some white jockeys physically threatened their African-American colleagues — even on the track, said Kentucky Derby Museum curator Chris Goodlett.

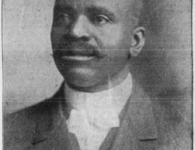

Winkfield, in particular, experienced episodes of physical intimidation while racing.

“You had instances of jockeys, white jockeys, kind of ganging up on him during the race, riding him close to the rail—which could hurt him, could hurt the horse,” Goodlett said.

The tactics affected the jockey’s career opportunities.

“As far as trainers and owners are concerned, if other riders are ganging up on their jockeys, they don’t necessarily want to ride that jockey,” he said.

The world outside of racing was also changing. The rise of Jim Crow laws in the South prompted many black Americans to migrate north, where they were more likely to find work in factories than on farms. Knowledge of horses was lost as new generations grew up in cities.

Jimmy Winkfield himself rode Alan-a-Dale across the finish line in 1902. No black jockey has won the Kentucky Derby since. And for a while, the contributions of African Americans to horse racing was largely forgotten. But there are those who still honor them.

Shirley Mae Beard owns Shirley Mae’s Cafe in Louisville’s historically black Smoketown neighborhood. In 1989, she started an annual “Salute to Black Jockeys Who Pioneered the Kentucky Derby,” complete with carnival rides and farm animals.

Her event went on for years, and attracted celebrities like Whoopi Goldberg and Morgan Freeman. Photographs of black racing pioneers still decorate the cafe’s walls.

“The black jockeys were role models for the young black men. When we realized that people didn’t know about the black jockeys, that’s when we started the celebration,” Beard said.

Read More At http://wfpl.org/how-black-jockeys-went-from-common-to-rare-in-the-kentucky-derby/

No comments