Massachusetts was the first slave-holding colony in New England, though the exact beginning of black slavery in what became Massachusetts cannot be dated exactly. Slavery there is said to have predated the settlement of Massachusetts Bay colony in 1629, and circumstantial evidence gives a date of 1624-1629 for the first slaves. “Samuel Maverick, apparently New England’s first slaveholder, arrived in Massachusetts in 1624 and, according to [John Gorham] Palfrey, owned two Negroes before John Winthrop, who later became governor of the colony, arrived in 1630.”[1] The first certain reference to African slavery is in connection with the bloody Pequot War in 1637.

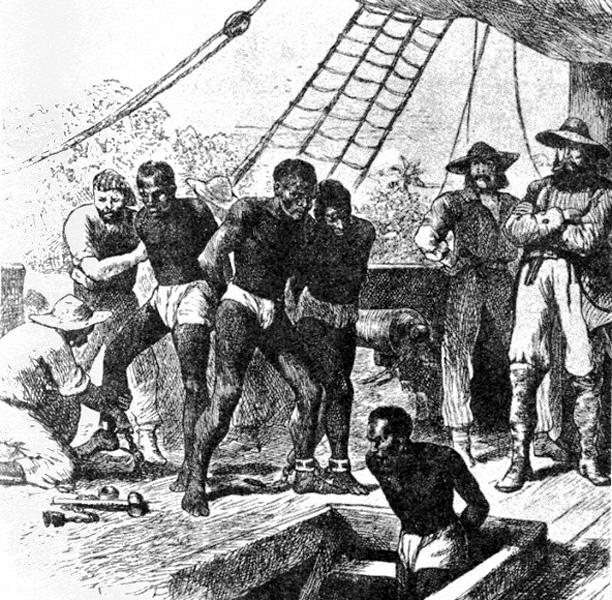

The Pequot Indians of central Connecticut, pressed hard by encroaching European settlements, struck back and attacked the town of Wetherfield. A few months later, Massachusetts and Connecticut militias joined forces and raided the Pequot village near Mystic, Connecticut. Of the few Indians who escaped slaughter, the women and children were enslaved in New England, and Roger Williams of Rhode Island wrote to Winthrop congratulating him on God’s having placed in his hands “another drove of Adams’ degenerate seed.” But most of the men and boys, deemed too dangerous to keep in the colony, were transported to the West Indies aboard the ship Desire, to be exchanged for African slaves.

The Desire arrived back in Massachusetts in 1638, after exchanging its cargo, according to Winthrop, loaded with “Salt, cotton, tobacco and Negroes.” “Such exchanges became routine during subsequent Indian wars, for the danger of keeping revengeful warriors in the colony far outweighed the value of their labor.”[2] In 1646, this became the official policy of the New England Confederation. As elsewhere in the New World, the shortage and expense of free, white labor motivated the quest for slaves.

In 1645, Emanuel Downing, brother-in-law of John Winthrop, wrote to him longing for a “juste warre” with the Pequots, so the colonists might capture enough Indian men, women, and children to exchange in Barbados for black slaves, because the colony would never thrive “untill we gett … a stock of slaves sufficient to doe all our business.”[3] Most, if not all, of the limited 17th century New England slave trade was in the hands of Massachusetts. Boston merchants made New England’s first attempt at direct import of slaves from West Africa to the West Indies in 1644, but though the venture was partially successful, it was premature because the big chartered companies still held monopoly on the Gold Coast and Guinea.

By 1676, however, Boston ships had pioneered a slave trade to Madagascar, and they were selling black human beings to Virginians by 1678. For the home market, the Puritans generally took the Africans to the West Indies and sold them in exchange for a few experienced slaves, which they brought back to New England. In other cases, they brought back the weaklings that could not be sold on the harsh West Indies plantations (Phyllis Wheatley, the poetess, was one) and tried to get the best bargain they could for them in New England. Massachusetts merchants and ships were supplying slaves to Connecticut by 1680 and Rhode Island by 1696.

The break-up of the monopolies and the defeat of the Dutch opened the way for New England’s aggressive pursuit of the slave trade in the early 1700s. At the same time, the expansion of New England industries created a shortage of labor, which slaves filled. From fewer than 200 slaves in 1676, and 550 in 1708, the Massachusetts slave population jumped to about 2,000 in 1715. It reached its largest percentage of the total population between 1755 and 1764, when it stood at around 2.2 percent. The slaves concentrated in the industrial and seaside towns, however, and Boston was about 10 percent black in 1752.

Read More: Slavery in Massachusetts

1 Comment

So slavery grew out of them being lazy not wanting to do their own work, and look at Congress today. Now tell me history want teach you something? It’s very sad