Photo credits: The Library of Congress (Hispanic Division)

On March 22, 1873, slavery was abolished in Puerto Rico with one significant condition. The slaves were not emancipated; they had to buy their own freedom, at whatever price was set by their last masters. The law required that the former slaves work for another three years for their former masters, other people interested in their services, or for the state in order to pay some compensation.

The former slaves earned money in a variety of ways: some by trades, for instance as shoemakers, or laundering clothes, or by selling the produce they were allowed to grow, in the small patches of land allotted to them by their former masters. In a sense, they resembled the black sharecroppers of the southern United States after the American Civil War, but the latter did not own their land. They simply farmed another’s land, for a share of the crops raised. The government created the Protector’s Office which was in charge of overseeing the transition. The Protector’s Office was to pay any difference owed to the former master once the initial contract expired.

The majority of the freed slaves continued to work for their former masters, but as free people, receiving wages for their labor. If the former slave decided not to work for his former master, the Protectors Office would pay the former master 23% of the former slave’s estimated value, as a form of compensation.

According to modern Latin American historians, the first Africans came to Puerto Rico as slaves in the mid-1500s.

The Treaty of Paris of 1898 settled the Spanish–American War, which ended the centuries-long Spanish control over Puerto Rico. Like with other former Spanish colonies, it now belonged to the United States. With the United States, control over the island’s institutions also came a reduction of the natives’ political participation. In effect, the U.S. military government defeated the success of decades of negotiations for political autonomy between Puerto Rico’s political class and Madrid’s colonial administration. Puerto Ricans of African descent, aware of the opportunities and difficulties for blacks in the United States, responded in various ways.

The racial bigotry of the Jim Crow Laws stood in contrast to the African American expansion of mobility that the Harlem Renaissance illustrated.

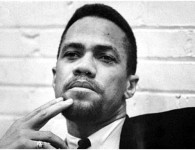

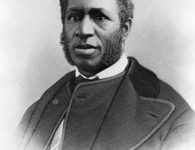

One Puerto Rican politician of African descent who distinguished himself during this period was the physician and politician José Celso Barbosa (1857–1921). On July 4, 1899, he founded the pro-statehood Puerto Rican Republican Party and became known as the “Father of the Statehood for Puerto Rico” movement. Another distinguished Puerto Rican of African descent, who advocated Puerto Rico’s independence, was Arturo Alfonso Schomburg (1874–1938). After emigrating to New York City in the United States, he amassed an extensive collection of preserving manuscripts and other materials of black Americans and the African diaspora.

He is considered by some to be the “Father of Black History” in the United States, and a major study center and collection of the New York Public Library is named for him, the Schomburg Center for Research in Black Culture.

He coined the term Afroborincano, meaning African-Puerto Rican.

No comments