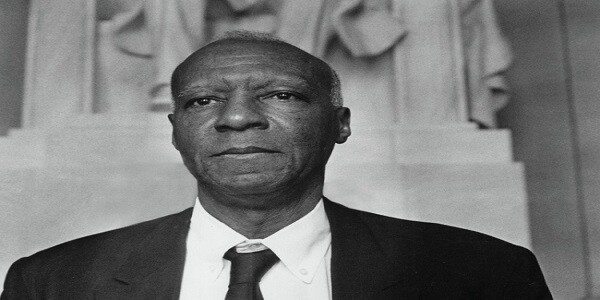

Photo credits: Rowland Scherman

On May 1, 1941, Asa Philip Randolph (pictured), the black leader of the Brotherhood of Sleeping Car Porters, promised a “thundering march” of 150,000 blacks on Washington “to wake up and shock white America as it has never been shocked before.”

He determined that such a massive public event was the best way to persuade President Franklin D. Roosevelt to assure a racially inclusive workplace in the fast-growing military businesses and federal government bureaucracies of the United States. President Roosevelt signed Executive Order 8802, which established the Fair Employment Practices Committee (FEPC) to prevent racial discrimination in federal employment, only days before the planned march. Randolph, then it called off.

The sole formation of a new government institution, however, did not guarantee justice. Randolph maintained demand on the government to give the FEPC with an ample budget and manpower. The FEPC could not control private companies or labor unions, despite the fact that black employment in government occupations surged from 60,000 in 1941 to 200,000 in 1945.

“We call upon you to fight for jobs in National Defense. We call upon you to struggle for the integration of Negroes in the armed forces. We call upon you to demonstrate for the abolition of Jim-Crowism in all Government departments’ defense employment. This is an hour of crisis. It is a crisis of democracy,” Randolph wrote in his proposal statement to the president titled The Call to Negro America to March on Washington.

“It is a crisis of minority groups. It is a crisis for Negro Americans. What is this crisis?” he continued.

Despite the FEPC’s shortcomings, proposals to establish it as a permanent government body received little political support.

No comments