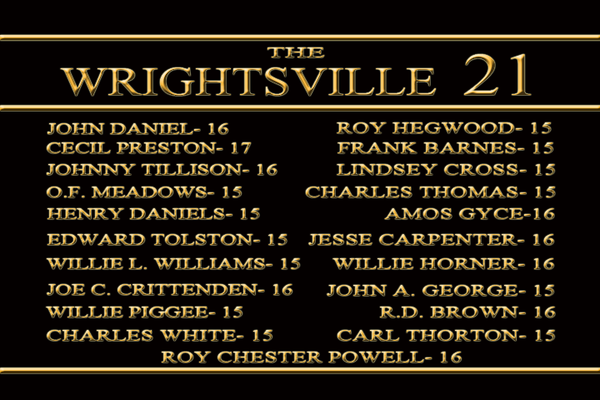

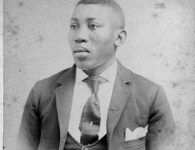

On March 5, 1959, twenty-one African-American boys burned to death inside a dormitory at an Arkansas reform school in Wrightsville (Pulaski County). The doors were locked from the outside. The fire mysteriously ignited around 4:00 a.m. on a cold, wet morning, following earlier thunderstorms in the same area of rural Pulaski County. The institution was one mile down a dirt road from the mostly #black town of Wrightsville, then an unincorporated hamlet thirteen miles south of Little Rock (Pulaski County). Forty-eight children, ages thirteen to seventeen, managed to claw their way to safety by knocking out two of the window screens. Amidst the choking, blinding smoke and heat, four or five boys at a time tried to fight their way forward through the narrow openings as the fire began to devour them. Survivors never forgot the horror of that fire. The wife of one of the survivors later said, in an interview before her husband’s death from cancer, that he had continued to dream about the fire.

The event brought attention to this largely forgotten institution that was operating during the Jim Crow era in Arkansas. Founded in 1923, the Arkansas Negro Boys Industrial School (NBIS) was, for most of its existence, a juvenile work farm located first outside Pine Bluff (Jefferson County) and then, in the mid-1930s, outside of Wrightsville.

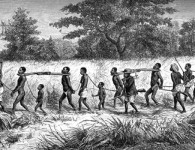

The institution became “Exhibit A” for the disparities that prevailed in Arkansas during segregation. Throughout the history of segregation, government employees, historians, and sociologists documented differences in the philosophy and physical structures of the white and black institutions in the state. For example, the 1940 biennial report to the governor notes the following vocational trades taught at a white boys’ school: “carpentry and joining, cabinet work, glazing, painting cement work, brick laying, wood and metal lathe operation, blacksmithing, acetylene welding, plastering, tailoring and shoe mending.” NBIS is mentioned only once—as the recipient of 156 mattresses made by the white boys’ trade school. By the time of the fire, the differences had only marginally narrowed.

A 1956 report by sociologist Gordon Morgan documented the horrific conditions at Wrightsville. It was not merely that “vocational education suffers greatly at the school.” The squalor was mind boggling: “Many boys go for days with only rags for clothes. More than half of them wear neither socks nor underwear during [the winter] of 1955–56….[It is] not uncommon to see youths going for weeks without bathing or changing clothes.” At times, the number of boys at the “school” was over 100. There was no laundry equipment. A single thirty-gallon hot water tank served the bathing needs of the entire population. The water was deemed undrinkable. Employees brought their own drinking water to work.

As an institution for black male delinquents and orphans in an era in which penal conditions were particularly notorious for their routine cruelty and corruption, Wrightsville resembled in some unsettling ways the infamous Arkansas adult prison farm in southeastern Arkansas, popularized in the 1980 movie Brubaker. Wrightsville had all the hallmarks of a junior prison work farm in the making. At the time the decision was made to move NBIS to Wrightsville, the Arkansas General Assembly formally decided that the best treatment for black boys sentenced to the institution was farming. Morgan, the sociologist who had worked on the 1956 report on the school, would later become the first tenured African-American professor at the University of Arkansas (UA) in Fayetteville (Washington County). He wrote in his master’s thesis on NBIS that, in an earlier era, armed guards had overseen the boys in the fields. Boys were whipped with a leather strap for infractions.

Read More Of This Article @http://www.encyclopediaofarkansas.net/

No comments