Photo credits: Archives Center, National Museum of American History, Smithsonian Institution

Reference: Steptoe, T. (2007, January 19). Mary Church Terrell (1863-1954). BlackPast.org. https://www.blackpast.org/african-american-history/terrell-mary-church-1863-1954/

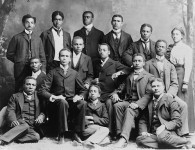

Mary Church Terrell (pictured) was the first president of the National Association of Colored Women. She was also an author, women’s rights activist, lecturer, and a civil rights activist.

Church, whose given name within the family was “Mollie,” was born in Memphis, Tennessee on September 23, 1863. Her parents were both freed slaves who financially found success in the marketplace. Her mother, Louisa Ayres Church, had a successful beauty parlor, and her father, Robert Reed Church, was the first black billionaire in the South via his successful commercial and real estate ventures. Church and her brother were little when their parents split up, and their father quickly remarried.

Church relocated from Memphis, Tennessee, to the Antioch College experimental school in Yellow Springs, Ohio, when she was a little child. She stayed in the Buckeye State to get her BA in classical languages from Oberlin College in 1884 after attending Oberlin Academy. Four years after that, she went to Oberlin and got her master’s.

Church graduated from Oberlin and entered the teaching profession over her father’s opposition. She started her career as a teacher at Ohio’s Wilberforce College before relocating to Washington, D.C. in 1887 to teach at M Street Colored High School (later renamed Dunbar High School). She also met her future husband, language department head Robert Heberton Terrell, and colleague Anna Julia Cooper when they were both working in Washington. Church had to leave her teaching position in Washington, D.C. after she was married there in 1891 because of the city’s discriminatory policies against married women.

Mrs. Church-Terrell became an activist a year after her wedding when horrific events in her community shook her. Thomas Moss, a close acquaintance from Memphis, was lynched in 1892, and she found out about it. When her pleas to President Benjamin Harrison for a public denunciation of lynching were ignored, she founded the Colored Women’s League in Washington to address social issues affecting black communities. Four years later, Mrs. Terrell was instrumental in establishing the National Association of Colored Women (NACW) and serving as its first president. The NACW’s slogan was “Lifting As We Climb,” and its mission was to advance racial equality via advocacy and educational opportunities for everyone.

From 1896 until 1901, Terrell served as president of the NACW, during which time she gained notoriety as a speaker and writer both domestically and internationally. Despite segregationist efforts to limit the participation of black women in the suffrage campaign, she continued to advocate for women’s suffrage. Terrell spoke up at NAWSA meetings in 1898 and 1900, when she emphasized the need for African Americans to overcome sexual and racial discrimination. She gave a lecture to the International Council of Women in German when she was visiting Germany in 1904.

Terrell provided assistance to many political campaigns. She was the head of the Women’s Republican League in the nation’s capital and a devoted member of the Republican Party. Moreover, she agreed to lead a Republican Party initiative to empower black women in the East. Additionally, from 1895 to 1901 and again from 1906 to 1911, Terrell volunteered his time to serve on the Washington State Board of Education. When the NAACP was founded in 1909, it was thanks to Terrell’s signature on a charter (NAACP).

Terrell utilized her writing to further her social and political interests in addition to her work as a founder and head of several organizations. Numerous periodicals and magazines published her essays, poetry, and short stories focusing on issues of race and gender. In her autobiography, A Colored Woman in a White World, published in 1940, she chronicles her personal experiences in the United States, which comprised of being oppressed based on her race, as well as being a woman.

Following WWII, Terrell became involved in the growing movement to abolish legal segregation in the nation’s capital. She saw the year 1953, when Washington, DC’s segregated restaurants first opened to all patrons. Public school segregation was declared unlawful by the Supreme Court a year later. About two months after the ruling was issued, on July 24, 1954, Mary Church Terrell passed away in Highland Beach, Maryland (Steptoe, 2007).

She was 90 years of age at the time of her death.

No comments