Intro by Victor Trammell

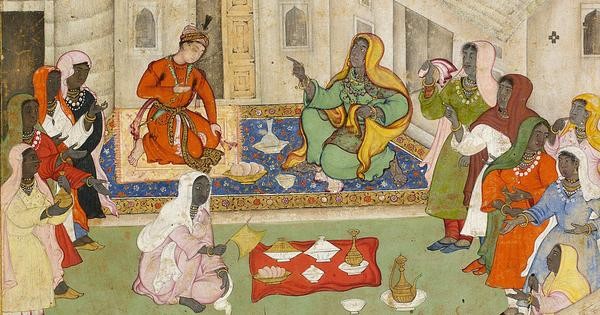

Photo credits: Francesca Galloway

Modern historians (such as Kenneth Robbins of the Schomburg Center for Research in Black Culture of The New York Public Library) claim that the first Africans began arriving on the subcontinent of India as slaves and traders early in the Fourth Century.

By the time the 14th Century came around, Africans had established themselves very well in India. From this time until around the 17th Century, black Africans in India were experiencing a golden era. They flourished as major contributors to Indian society who helped politically shape the country’s history.

“Deccan sultans relied on African soldiers because Mughal rulers of northern India did not allow them to recruit men from Afghanistan and other central Asian countries,” Robbins said in an interview with BBC.

However, on the account of other historians, racism against blacks in India superseded the hatred they experienced in subjugation to white Europeans. An American journalist of Indian descent named Sabrina Malhi published a report recently about the history of anti-black racism in India and how it continues to exist today.

Here’s her story:

(as told at TheJuggernaut.com)

The ancient Hindu epic, the Mahabharata, describes Draupadi, one of the most well-known female figures, as a “dark beauty.” Growing up, she hated her dark skin color, but Krishna tells her that the darkness of her skin — which is described as syama (or blue-black) — was auspicious and a color used to represent the divine. In Islam, Prophet Mohammed’s most loyal companion, Bilal ibn Rabah, is said to have been despised by the Prophet’s tribe due to his dark complexion, because he was the “son of a slave.” These ideations surrounding race and identity have been a key point of discussion amid today’s climate.

Since George Floyd’s death at the hands of Minnesota police officer Derek Chauvin on May 25, anger flowed across the nation, as communities came together to protest in solidarity. South Asians have also stridently voiced their disdain of the systemic oppression against black people in America. Yet, the South Asian community has also been part of a long history of casteism, colorism, and racism — traced back to ancient times. But others argue this shouldn’t be an excuse to not confront racism today.

Portrayals of darker-skinned people as a lower part of society goes back to pre-colonization in India and globalization, according to Smitha Radhakrishnan, an ethnographer at Wellesley College. However, Radhakrishnan said that while both colorism and the caste system have pre-colonial histories, the colonization of the Indian subcontinent lasted for many centuries, so it’s tough to pinpoint when these sentiments first emerged. “British rule strengthened colorism such that it came to seep into every aspect of the dominant cultures in South Asia over time,” she said.

Indrani Chatterjee, a scholar on the history of slavery, gender, and law in the histories of South Asia, said that, in Vedic times (1500 B.C.E. to 500 B.C.E.), people were categorized by moral-ritual ranks instead of by skin color or looks. “There are no explicit examples of anti-blackness as we know it now until the 18th century,” Chatterjee said.

The concept of anti-blackness is also missing during the early days of the Indian Ocean slave trade, which dates back to the sixth century, when Arab Muslims were primarily responsible for the movement of Africans across the Indian Ocean. Back then, South Asians considered Africans, who served as special servants, midwives, or herbalists at the courts of nawabs and sultans, to be prestigious. The slave trade then switched hands to the Portuguese, Dutch, French, and British.

Portuguese invaders of the subcontinent in the 16th century first categorized people based on skin color. “Racial terms about descent groups [were] divided by ‘blood.’ That was what they meant by ‘casta,’” Chatterjee added. “This is how the Portuguese observers used to describe the various groups they met in their Indian outposts in the 16th century.” However, it wasn’t until after the 18th century, when the British East India Company’s rule began in India, that the Portuguese classificatory system became the dominant way of framing people in South Asia.

“Colorism was an inherent part of the history of global capitalism and the squeezing of labor from different groups of people,” Chatterjee added. Using color as a determining factor was a seemingly easy way to divide and an obvious way to define people.

“Ideas of race were used by the British to control and separate people in India,” said Sravanthi Kollu, a scholar of South Asian literature and history at Harvard University.

Kollu refers to Herbert Hope Risley, a controversial British anthropologist who charted facial and physical measurements of people in India, then distributed them across the continent. “It was one of the most apparent ways of racial hierarchy,” she said. Kollu also adds that these racial hierarchies don’t appear in a vacuum — the caste system still played a significant role.

It’s harder for people in the South Asian community to truly understand their inherent biases, because it’s something that’s not openly discussed. “The South Asian community does not foreground the diverse histories of migration that make up the community,” Kollu said. “The way to reflect on this complicated history would be first to make its complexity more visible in general conversations.”

Other scholars, such as Harvard’s Suraj Yengde, whose research focuses on the solidarity between Dalits and blacks, say that it wasn’t just outsiders — India gave birth to the original color-based social class system that dates back to the ancient Rig Veda texts, to around 1200 B.C. “The Varna system literally means ‘color’ system, so it’s not surprising that Indians in America have maintained these racist dogmas,” he said. Dalits and the black American experience have strong ties because they are the most disenfranchised people in their communities. “This whole situation is having a global ripple effect. I don’t know if it will bring about much change, but people are definitely talking about it.”

Yengde adds that the caste system and skin color are very much linked. “Oftentimes, we’ll see Brahmins push ideas of colorism, racism, casteism on British and Muslim invaders,” he said. That’s why Yengde doesn’t see the inherent bias of some South Asians going away anytime soon.

The early signs of anti-blackness in more modern South Asian history in America are evident in the landmark 1923 Supreme Court case, the United States v. Bhagat Singh Thind. Thind claimed that he should be granted citizenship because he was Aryan — thus, closer to whiteness — and a high-caste Hindu (despite being Sikh). He was denied citizenship, and subsequently, many citizens of Indian descent had their citizenship rescinded.

Dina Siddiqi, a New York University scholar on global liberal studies, believes that many South Asians present themselves closer to whiteness. “Anti-blackness works to secure a kind of civilizational superiority. And it sits comfortably with colorism and casteism imported from the home country,” Siddiqi said.

In recent times, many South Asian Americans have shied away from overt displays of racism but still have an implicit bias — expressed via anti-black dating preferences, cultural appropriation, and microaggressions. South Asian children often grow up hearing things like “don’t ever marry a black person” or “you’d be prettier if you had lighter skin.”

The quest for fair skin is still so prevalent in South Asian communities that it’s even a part of many wedding traditions. The haldi ceremony — a pre-wedding ritual ceremony using a turmeric paste for both the bride and groom to lighten the color of their skin — dates back thousands of years. Fashion designer Masaba Gupta once described how turmeric and other home remedies were part of her beauty routine designed to help lighten her skin color. “I’m like ‘that ain’t happening, you can’t scrub color off.’”

Later generations of South Asian migrants grew up with the skin-lightening cream Fair & Lovely. Hindustan Unilever released the cream in 1971 across South Asia. Fair & Lovely said that it surveyed women in India in the 1970s and found that “90 percent of Indian women want to use whiteners because it is ‘aspirational… A fair skin is like education, regarded as a social and economic step up.’” These melanin-suppressant creams have toxic physical side-effects, but they set the standard of beauty: fairer-skinned meant a better, more desirable person. It took until 2020 for the Indian government to make a legislative push to ban skin-whitening creams.

“There is an important distinction between ‘implicit bias,’ ‘colorism,’ and [a] ‘white supremacist’ ideology [that has] been absorbed by many educated Indians both in India and in the diaspora, especially in North America,” Chatterjee said.

That said, South Asian Americans have been increasingly part of the fight against anti-blackness.

“When our parents came into this country, it already had issues with white supremacy and racism so they were able to say ‘this is not my ancestors’ fault,’” shared Tara Cotton, a first-generation Indian American. “But now as we’ve emerged with more of an American identity, we realize while our ancestors might not be to blame for this, it’s our responsibility to fix the problem.”

Source: “Anti-Blackness Goes Back to Ancient Times” by S. Malhi; published by TheJuggernaut.com

1 Comment

[…] This content was originally published here. […]