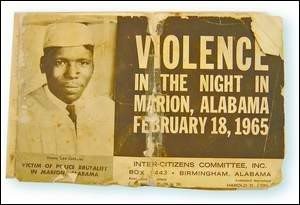

On a sunny March day in 2005, a retired Alabama state trooper quietly drinks his morning coffee outside on his deck in southern Alabama. He granted an interview to John Fleming of Anniston, Alabama. At age 72, James Bonard Fowler is asked about Jimmie Lee Jackson, a 26-year-old activist who he claimed he shot in self-defense on February 18, 1965. “My life was in danger and he was trying to kill me. I’d done it again if I had to,” said Fowler. Jackson died eight days later. But who was Jimmie Lee Jackson, and why is he relevant to the Civil Rights Movement?

Jimmie Lee Jackson is remembered as an eager, young twenty-six year old from the Black Belt of Alabama. He tried to register to vote several times, and because of racial discrimination in the South, he was denied each time.

Jimmie Lee Jackson is remembered as an eager, young twenty-six year old from the Black Belt of Alabama. He tried to register to vote several times, and because of racial discrimination in the South, he was denied each time.

On the night of February 18, 1965, Jimmie Lee Jackson, his eighty-two year old grandfather Cager Lee, and his mother Viola participated in a protest after a meeting at the Zion United Methodist Church in Marion. Alabama state troopers knew of the protest thanks to surveillance by the FBI. Outside, they were attacked. Wandering through the crowd, he finds his grandfather, and the two seek refuge in the nearby Mack’s Café. Inside, Viola Jackson was attacked by two state troopers and fell to the ground. Jimmie Lee’s plea to leave was ignored. While rescuing his mother, a trooper grabbed him and shoved him into a cigarette machine and shot him twice in the stomach. A witness to the shooting overheard one trooper ask, “Who got him?” Another responded “I got him.” This was James Bonard Fowler. Jimmie was taken to Good Samaritan hospital in nearby Selma. Several days later, Colonel Al Lingo of the state police walked into the hospital and served an arrest warrant to Jackson: assault and battery with intent to murder a police officer.

Jimmie Lee Jackson appeared to be on the way to recovery. At 9pm, as Dr. William Dinkins recalled, Jackson was sitting up in his bed talking and in good spirits. Thirty minutes later, Dinkins received a call from the hospital that another doctor had decided Jimmie needed to undergo further surgery. Dinkins argued against it but eventually was forced to proceed. During surgery, Jackson was under a safe dose of anesthesia. Minutes later, his blood turned dark and Dr. Dinkins stated to the other doctor that Jackson should be put on 100% oxygen. Instead the doctor decided to increase the levels of anesthesia and in minutes Jimmie Lee stopped breathing and died. Dr. Dinkins was adamant that Jimmie Lee Jackson could have survived had this second surgery not occurred.

The local black community was outraged. SCLC organizer James Bevel stated “We will march Jimmie’s body to the state capitol in Montgomery and lie it on the steps so Governor George Wallace can see what he’s done.” This did not happen. However, Bevel’s statement did spark an idea to march from Selma to Montgomery. The march would begin on a Sunday March 7, at the Edmund Pettus Bridge; four days after Jimmie’s funeral. The first march would end in violence, with disturbing images shown across the nation to millions of TV viewers. “Bloody Sunday” was the catalyst for the Voting Rights Act of 1965 to protect African-Americans from being denied the right to vote.

1 Comment

There wasn’t a United Methodist Church until the Methodists merged with the Evangelical United Brethren Church in 1968 so they could not have met at an UMC in 1965.