Lubertha Johnson was a Las Vegas community activist who helped other community leaders organize strikes.

Johnson was born in 1906 on a Mississippi farm, and raised by her grandmother. She had originally planned to be a teacher, but due to the Great Depression and her father’s ill health, she was instead forced to join her family in Chicago to help support them. Along with her family, Johnson moved to Las Vegas in 1943 where she found work as a recreational director at the federally funded Carver Park housing project. The Carver Park housing project provided shelter for the black workers at Basic Magnesium Incorporated (BMI), the plant that processed magnesium for aircraft and bombs during World War II.

While working at the housing project, Johnson took an active interest in African American life in Southern Nevada, based on her family’s belief that accomplishment came from education—and she accomplished a lot in Las Vegas. Johnson organized the Tenants Council at Carver Park which was her first major accomplishment as an activist. The Council organized discussion sessions around various topics, especially racial discrimination at the plant. These discussions led to black men organizing and staging a strike in October 1943.

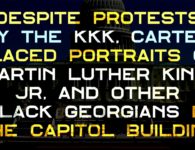

Johnson left Carver Park and became familiar with the Westside community, becoming active in the NAACP. She married in 1945 and she and her husband began looking to buy property, but they were only allowed to purchase land in the Westside community. Johnson later enrolled in nurse training courses and worked for seventeen years at Southern Nevada Hospital, gradually giving up all attachments to the ranch and moving into the city. Prior to the 1960s, public swimming pools, restaurants, hotels, and gambling establishments did not allow blacks to use the facilities. Movie theaters limited the areas where blacks could sit to either the back or a certain side of the auditorium.

Because Johnson was not fearful of speaking out against inequality as she did in Mississippi, she and her friends began to stage their own protests. They would sit in the center of movie theaters and restaurants where they would remain until the police arrived. Consequently, they were thrown out of many places.

“The act of protest that Johnson remembered best was when Josephine Baker performed at the El Rancho Hotel in the early 1950s under a contract that allowed an integrated audience. On the second night of her performance, the hotel stated that since they had adhered to the contract once, they would not have to allow blacks in on the second evening of her engagement. The fifteen or twenty black audience members, including Johnson, walked into the showroom with Baker but were refused service. So, Baker refused to perform; instead, she just sat on stage and did nothing. Once her black guests were served, she put on her show.”

Johnson’s greatest work materialized under a multi-faceted poverty program. She ran the portion of the program that sponsored the Head Start Initiative. She named it Operation Independence. She served as director for twenty-one years, retiring at the age of eighty-one, three years before she died in 1990.

source:

http://nevadahumanities.org/blog/lubertha-johnson

No comments