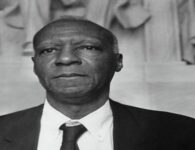

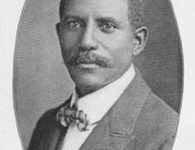

Angelo Herndon was the defendant in one of the most publicized and notorious legal cases of the 1930s. In 1932, nineteen-year-old Herndon was arrested under an obscure 19th century servile insurrection law for attempting to organize a peaceful demonstration of unemployed workers in Atlanta. Largely due to the efforts of the Communist Party-affiliated International Labor Defense, the arrest and subsequent trial ignited a firestorm of protest that, alongside the Scottsboro case, helped expose the gross injustice of the southern legal system and introduced African Americans on a broad scale to the militant anti-racism of the Communist Party.

Herndon was born on May 6, 1913 in Wyoming, Ohio, outside of Cincinnati. As a teenager he migrated to Kentucky and then Alabama in search of employment. It was in Birmingham in 1930 that he was first introduced to the Communist Party. Impressed by the Party’s uncompromising avowal of interracial unity, Herndon joined and began working with the local Unemployed Council. In 1931, Herndon briefly worked for the International Labor Defense on its campaign to free the Scottsboro defendants.

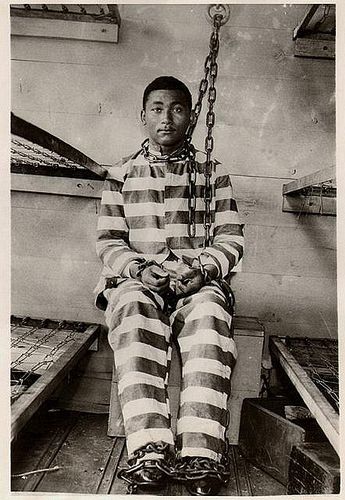

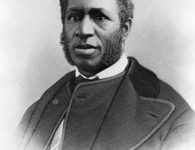

Herndon’s own trial began in January 1933. The ILD retained a young black attorney, Benjamin Davis, Jr., to lead the defense. Davis challenged the constitutionality of the insurrection law and the systematic exclusion of blacks from Atlanta’s jury rolls as well as the repeated use of racial slurs by both the prosecution and judge. Nevertheless, Herndon was convicted and sentenced to twenty years on a Georgia chain gang. Echoing its strategy in the Scottsboro case, the ILD augmented Herndon’s legal defense with mass demonstrations outside the courtroom in an attempt to apply political pressure on the legal system. After a four-year publicity campaign and appeals process, the U.S. Supreme Court overruled Herndon’s conviction and he was released from prison.

Herndon continued to be involved with both the Communist Party and civil rights activism for a time. He was elected as national head of the Young Communist League in 1937. In the early 1940s he partnered with Ralph Ellison to edit a short-lived periodical, Negro Quarterly. In the mid 1940s Herndon began to drift away from the CP and shrink from the public eye. He spent the remainder of his life working as a salesman in an undisclosed midwestern city.

Sources:

Charles H. Martin, The Angelo Herndon Case and Southern Justice (Baton Rouge: Louisiana State University Press, 1976); Angelo Herndon, Let Me Live (New York: Random House, 1937).

Contributor:

article found at: http://www.blackpast.org/aah/herndon-angelo-1913#sthash.C371ltOK.dpuf

No comments