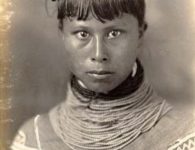

Photo credits: Pinterest/Christopher Jones

Christmas is a particularly long-lost occasion throughout the wake of a ubiquitous and contentious public discussion.

The back-and-forth dialogue inside the aforementioned discussion has raged on for many years. It debates interpreting the dark legacy of America’s former “Peculiar Institution,” as well as the proportional rate that it ought to be educated in today’s classrooms. History’s spin doctors have continued to pitch their failed theories as mainstream truths.

They believe in legitimizing an ancient illusion, which erroneously teaches that the Civil War’s battles were contended over legalizing the individual independence of state rights; not over outlawing the Peculiar Institution of U.S. slavery. These fable founders have sought to rewrite events, which occurred in the South while slavery was still legal.

Their attempts to whitewash textbooks also came around the historical period when Christmas began to gain countrywide acclaim as a federal holiday.

America’s recognizance of this ancient Pagan custom became official toward the end of the 1800s. In all reality, the Confederate South was beaten after the Civil War. Though its soldiers put up a good military fight, their quest for federalism failed.

However, Rebel enthusiasts who still had a degree of cultural visibility and relevance hoped to harness the public’s morale. They also wanted to wield power and gain clout inside the arena of national politics.

One of the ploys they used to achieve their aims involved the constant promotion of sugar-coated Christmas myths. These fictional narratives often depicted black slaves dancing, as well as eating with their white owners and their women.

The pro-Rebel spin-doctors also peddled tall tales about warm and festive gift exchanges on the plantations, which included black slaves, as well as the relatives of their slave owners.

These sanitized versions of events strengthened the often-pitched Confederate idea, which questionably stated how each enslaved black person in the Deep South admired their white slave owner and his or her spouse.

However, such a fallacy could not be farther from reality. Around holiday time, many black slaves feared being sold far away from their families. Others were terrified of being bloodied by the wanton cruelty of their master’s flesh-ripping whip. In other macabre circumstances, young slave boys and girls would be given as pet-like Christmas gifts.

Fortunately, a former black slave named Henry Bibb chose Christmas of 1837 as the day for his great escape to freedom.

In his 1849 memoirs, Bibb wrote that he paddled across a mighty river from Kentucky to Ohio. He described his journey toward justice as “a bolt for Liberty or consent to die a slave.” Bibb saw an open opportunity for liberation after his plantation owner allowed black slaves to work for themselves during the Christmas season.

During the research process, which he undertook to write his 2019 book titled Yuletide in Dixie: Slavery, Christmas, and Southern Memory, scholar Robert E. May combed through a plethora of evidence.

The authenticated evidence he came across proves that slavery’s holiday brutality in the U.S. was no myth. While on his research path, May obtained plantation owners’ diaries, magazines, memoirs, and heard oral presentations from individuals who were once slaves; in order to ascertain what really transpired on plantations around Christmas.

“It’s certainly timely in the sense of the debates that are going on right now,” May recently told TIME Magazine in an exclusive interview.

“Do you really bring up Christmas slave sales? Do you really bring up Christmas whippings or is that going to make part of your class feel bad or feel guilty? My answer is that we really do need to liberate teachers to address the past critically—not just about enslavement, but our whole history of race in America,” he continued.

Buy author Robert E. May’s book Yuletide in Dixie here.

No comments