Photo credits: The Associated Press

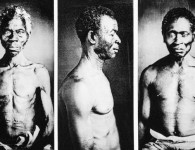

Three Black men, including a preacher, were banned from attending Easter Sunday services at numerous white churches in Jackson, Mississippi.

This occurred on March 29, 1964. After the white churches forcibly turned them away, two of the Black men and seven white pastors who had joined them were arrested and incarcerated. Their bail was set at $1,000 apiece. Ushers on the church steps refused to admit Methodist Bishops Charles Golden, a Black man, and James Matthews, a white man, inside the Galloway Memorial Church that morning, citing “church rules.”

The two bishops requested to talk with the church minister as high-ranking representatives of the Methodist Church, but the ushers refused. While the black attendees remained outside the church contemplating their options, an angry white mob taunted and jeered them until they fled the premises. Bishop Golden would subsequently criticize “those who pretend to speak and act for God in sending worshippers away from his house” in an interview.

Bishop Golden and Bishop Matthews were allowed to go. However, an interracial group of nine men was detained 10 blocks away at the Capitol Street Methodist Church during an Easter service. When the group of guys attempted to walk around the ushers on the church steps, they were detained and charged with trespassing and disturbing the peace. Two young Black males named Robert Talbert and Dave Walker were among the group, as were seven white men who had accompanied them to the service—clergy, theology instructors, and deans from numerous institutions and universities outside of Mississippi.

“To exclude any of those whom Christ would draw into himself from church…on Easter…because of color is a violation of human dignity,” the men said in a statement.

A court found all nine men guilty of “disturbing public worship” and sentenced them to six months in prison and a $500 fine the day following their arrests.

In reaction to recent violence against civil rights activists in St. Augustine, Florida, Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. and the Southern Christian Leadership Conference (SCLC) had announced preparations to conduct anti-segregation rallies there during Easter. Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. pushed civil rights activists in the North to come south to participate in “pray-in” and “kneel-in” protests at the city’s segregated churches, and that Florida effort certainly influenced the movement in Jackson. Several St. Augustine demonstrators were arrested—and even beaten—for attempting to combine Easter services at all-white churches, similar to what happened in Mississippi.

Even a decade after the Brown v. Board of Education ruling, many white churches remained firmly dedicated to racial segregation as a fundamental component of white supremacy and racial inequality, as seen by their prejudiced treatment of those attempting to attend church. Congress approved the Civil Rights Act of 1964 three months later, in June 1964, outlawing discrimination on the basis of race, color, religion, sex, and national origin.

However, the statute did not instantly eliminate white Americans’ tremendous opposition.

No comments